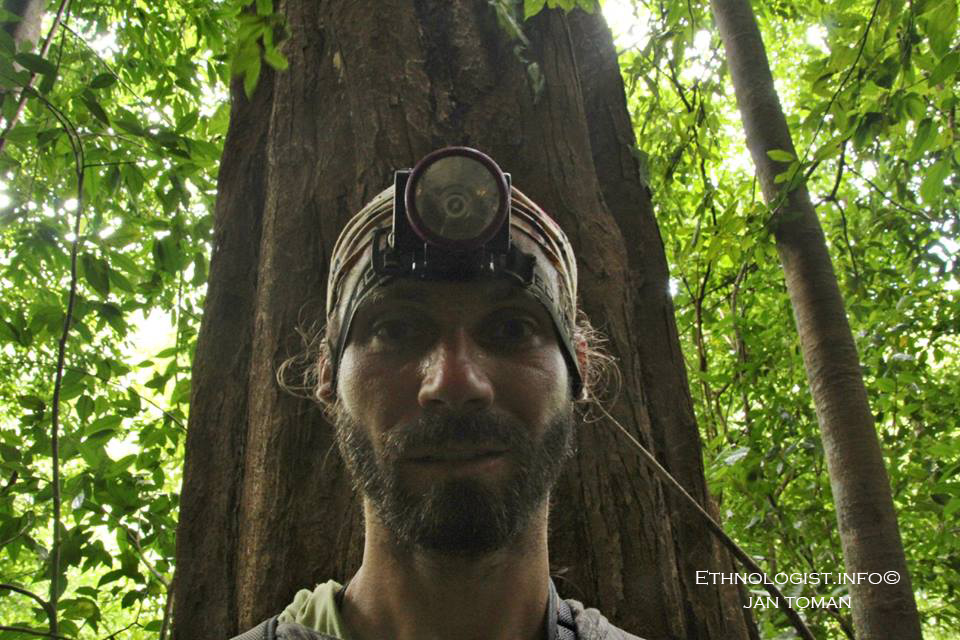

Jan Toman: I quit my job and bought one-way flight to Thailand

Jan Toman has a lifelong passion for travelling and visiting new countries. After his university studies in Ethnology at Charles University in Prague he worked in Czech museums and enjoyed his work with cultural collections. However, after 5 years he made the decision to travel across Southeast Asia and turn everyday life into an adventure, quitting his full-time job in a museum in Prague. Initially he did not know how long he would spend on his journey; in the end he spent 13 long months in Asia, visiting Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia and Brunei. As well as backpacking across the region, he worked on a number of organic farms and also as a teacher of English in Vietnam.

Along the way he photographed the traditional practices of Lao, Khmu, Hmong, Akha and Tay people. In Malaysia, a community of Burmese refugees welcomed Jan as if he were one of the family and he was even asked to introduce their church service and prayers. He visited a Cambodian school founded by Veronika Pospisilova and the Hvezdice charity, where he took photos to support the project. And finally, he visited a number of national parks and reservations, including an elephant hospital that takes care of elephants who have stepped on mines along the Thai-Burmese border.

What was the first country you visited while backpacking?

First I travelled to Thailand, and my whole journey continued from there. My initial idea was to spend three months in Thailand and my plans were open after that. I really wasn’t sure how long I would spend in Southeast Asia. In the end it turned into a 13-month journey.

I’ve seen your photos of the ‘Farm of Happiness’, part of the wwoof programme (world wide opportunities on organic farms). Can you tell me about your experiences on this farm?

This was a really great place to begin my cultural trip because I got to know more about local Thai culture there, in a way that few foreigners get to see. This organic farm is located in southwestern Thailand between Ratchaburi and the Burmese border. The farm is small and the business is still being developed. It’s not a place that’s sought after by tourists, because in theory there is little of note to see there, but that’s not to say that for an ethologist and adventure traveller there was nothing of interest!

Could you describe the family you stayed with and the people you met there? Many people have the misconception that there are no organic farms in Thailand or that the Thais do not like organic sustainable living or working hard on farms.

The farm is run by Mr Pisíj Gulapozee, who has led a very interesting life because he tried many jobs before embarking on farming. What is really interesting is that Pisíj was originally an IT technician for Thai radio, perhaps one of the first IT technicians in Thailand. After that he managed a tourist resort and then was a director of a business in Bangkok.

There was a connection between us and a common interest for travelling and I would say that Pisíj is a very mindful person and aware of ecological problems. He also travelled across Thailand before settling down to a family life with his wife and son on the farm. He wants to grow varieties of crops in harmony with nature and without using any pesticides – in so doing he wants to protect nature. He also runs a small shop to earn a livelihood to provide for his family. Their idea is to sell the produce grown on the farm.

And what was his reason for moving to the countryside, to start an ecological family business?

The main reason was his son’s health problems and the desire to live a happier life in a cleaner and healthier environment.

It seems to me that it was a happy opportunity that you met Mr Pisíj.

I would say that it was extraordinarily fortunate because Pisíj gave me useful advice about being prepared and careful in Thailand. I liked that he was able to think critically about Thai people. For example, he warned me that in Thailand tourists are seen as ‘money-making machines’ and try to take as much money as possible. I would say that it’s true, but only in the main tourist centres are Europeans really seen as ‘walking wallets’.

How did you find this organic farm? Did you arrange the stay before you travelled out there?

Yes, I found the farm through the wwoof organisation and I received a positive response. The family were so thrilled that I was interested in working with them as I was their very first volunteer.

How did they welcome you? And what did you think about the local people when you first met them?

As I say, I had a great advantage in that I was the first volunteer on this farm, and they wanted me to enjoy my work. From the very first day, they introduced me to Thai culture and food and I experienced Buddhist prayer at a temple too. The people on the farm were very nice, extremely open and they wanted to help me at all times.

I wonder how much people in the Thai countryside are aware of organic farming? Do they perceive its importance and usefulness?

I was very surprised to see that in this particular area, people have a relationship with organic farming and permaculture, and are trying to establish a number of ecological farms. This is also due to the fact that the late King Rama IX, who was the longest reigning King and an extraordinary man, travelled around Thailand and taught people how to cultivate the land and grow crops, even in areas where people grew only opium! Many Thai people say that they want to follow in the late King’s footsteps.

The current ruler is the son of Rama IX, and although he is known mainly as a great womaniser, he also promotes organic farming and sustainable agricultural methods. Now, however, Pisíj and his family are in some conflict with their relatives, who live just next door. That family use a lot of chemicals on their farm, which could reach and affect Pisíj’s land. This is a problem because for ordinary people it can be very difficult to change their minds and switch to organic farming methods.

Mr Pisíj Gulapozee also showed me other organic farms, for example one farm with land given over to growing bamboo and fruit and the rest left to be wild jungle. This was really exceptional. Everything growing there was doing so in some kind of symbiotic way. The owner is an elderly gentleman and he complained a lot about the devastation of the forests for profit. He himself did not want to make more money and he decided to protect nature instead. I really appreciate this attitude, especially in an Asian country.

Some of your photos show how people build houses in Thailand. Did you take these photos at Mr Pisíj’s farm too?

No – one day Mr Pisíj took me on a trip to a place I didn’t know. When we arrived I saw the locals building some kind of summer house. This seemed to be evidence to dispel the cliché that Thai people are lazy and that it is rare to see them working. I really liked how the people were working together, beautifully creating the complete structure. These people also took me on a traditional fishing trip after they had finished their work, which was a kind of celebration. They baked the fish they caught on a fire and celebrated with great energy. I’d say this experience led me to see Thailand from a completely different point of view.

Your photos are full of beautiful portraits of people and they emanate positive energy. Was this the case in reality?

It was, but I must admit that it is more the case in places where people are living in harmony with nature and where they help each other as a community.

How did you like Thai cuisine? Was it easy for you to eat in Thailand?

I think Thai cuisine is excellent. I don’t actually like many Czech dishes (my national cuisine). In contrast, I really enjoyed most Thai dishes. I like their traditional fried pad Thai noodles. I only have positive things to say! From all the countries I have visited, Thai cooking is my favourite!

Where was the next place on your journey?

The next place was another organic farm, the Homtel farm, a large, developed permaculture with many volunteers. Homtel farm is located near Khao Yai National Park, which is probably the most beautiful place I saw in Thailand. It is Thailand’s oldest national park and is covered in primary rainforest with diverse fauna and flora.

So the Khao Yai National Park was the most beautiful place you visited in Thailand?

Definitely, for me, yes. I prefer the landscapes inland, as opposed to the popular beaches and sea. I tend to seek out non-commercial places where there are beautiful forests, for example, with waterfalls and wild animals. This park is really remarkable and is home to 400 wild elephants.

Could you describe the Homtel farm in more detail?

The farm is run by a couple, a Thai man and a Thai-American woman (I think she was a daughter of American soldier, who settled there after the war). As it is a large farm, they distribute the various jobs among volunteers. They grow a variety of fruit, vegetables and plants, they have a large flock of sheep, and also a pond with fish. In the future, they want to grow organic coffee. Interestingly, their farm is spread over an area that was long ago destroyed by illegal mining, so they are trying restore this area.

You mentioned that you were part of a larger group of volunteers. What kind of people are most interested in this job and where do they come from?

To be honest, many volunteers travel to organic farms to save money. In terms of nationalities, many people come to work on farms from Western Europe: Germans, French, Dutch, Spaniards, or English. I also met Americans, and even an Egyptian in Malaysia, which was an interesting rarity for me.

You ended up spending four months in Thailand. How do you feel about the country overall?

Definitely positive overall. On the other hand, I don’t agree with the opinion that Thailand is the greatest paradise on Earth. Overall, I preferred the northern part of Thailand, where I had the opportunity to know local people. I enjoyed travelling in inland, exploring nature, the mountains and local villages. The North is better for these purposes. In contrast, the South of Thailand is more commercial and geared towards tourists, prices are higher there and people are not as friendly as in the North.

You didn’t spend a lot of money. How did you manage to get by?

I saved on transport, for example. In Thailand I travelled by hitchhiking. The first day of my journey, in Bangkok, my French roommate at the hostel recommended that I do this – he told me that it’s easy and almost everyone will stop.

The comical aspect about hitching in Thailand is that many people don’t really understand it and they stop because they think that you have some problem and you are calling for a help. In the best case scenario, they want to take you on to a bus stop; in the worst – when they do not understand English – they want to take you to the police station!

Many Thai people absolutely didn’t understand that I was hitchhiking because I enjoy travelling like this. The best thing is to ask someone to write you a message in Thai to give to the driver, explaining the reasons for your way of travelling.

After all, Thailand is a country renowned for hitchhiking by backpackers. I managed 500 or 600 km per day! And if you are a volunteer, you have free accommodation and food, so you will save a lot of money. Also I often slept outside official accommodation places – for instance, I slept in a Buddhist temple in Thailand. Thanks to all this, I saved a great deal of money.

Did the hitchhiking really excite you that much?!

Yes, and it’s not only about saving money! It lets you prolong your travel and discover new places or meet new people. It gives you wonderful experiences and memories.

What other places did you visit after working on organic farms?

As I said, I travelled mainly across the northern part of Thailand. I visited several national parks and monuments such as the historic city of Ayutthaya, home to the famous Buddha statue intertwined in the roots of trees, and the remarkable remains of the historic city Sukhothai, which means ‘dawn of happiness’ – unfortunately you can’t avoid the tourist crowds there. Then I travelled to a few places in the south of Thailand and then on to Laos.

Before we talk about Laos, could you tell me something about the elephant parks and elephant hospital you visited?

Sadly I have to say that elephants in Thailand are not doing very well and are being abused. I understand that elephants were used in logging in the past, which was a difficult time for the animals, but in today’s modern times the fact that they are forced to carry tourists and serve as a fun attraction seems terrible to me. I don’t understand why tourists would pay money for something like that. Perhaps many people don’t realise that baby elephants are taken from their mothers and are trained from ‘childhood’ to obey orders. Elephants are cognitively complex animals and highly dependent on their community, which is disrupted by the death of an individual elephant or by taking one into captivity. Needless to say, they show feelings of grief and are dependent long term on parental care.

Of course, some people say that this actually protects elephants, from poachers for example, and the truth is that it gives people jobs in Thailand. However, I really think that is possible to create an economy with elephants in a completely different way and that means by protecting them, such as in elephant sanctuaries, where the elephants are not abused and they can enjoy a life of relative freedom. In these sanctuaries you can take a bath with the elephants, for example. But here is the problem: it’s more expensive than riding an elephant in an amusement park or taking photos with them. So far, sanctuaries are not so sought-after, but I see great potential and that the best protection for the elephants lies in these sanctuaries in the future.

In contrast, there are perhaps only two places where you can ride elephants in Malaysia. There are more elephant sanctuaries there. I visited one of them and it looked more like a zoo, it was huge space and nobody bothered the elephants at all! Malaysia is more developed than Thailand on this score and is more aware that treating elephants as they do in Thailand is problematic.

What was the situation at the elephant hospital?

There was an elephant who had stepped on a mine on the Thai–Myanmar border, for example. This elephant had lost her leg and was being treated at this hospital. The workers had made her a prosthesis and were taking care of her. I really liked it.

So the elephant hospital was not part of the amusement park you mentioned?

No, it was a different organisation.

What were your initial impressions of Laos?

I must say, positive. At first, the people seemed more open and kinder to me than in Thailand. Even small children greeted me on the streets, but over time I realised that they are not so open. However, we have to understand that Laos is one of the last four countries to call itself Communist and it has not been welcoming tourists for long. They are not used to tourists. In some places I felt even that they were afraid of me, or that they saw me only as a ‘walking wallet’. But of course everything is changing rapidly. Also, Laos is one of the least developed countries in Southeast Asia. China is now investing a lot in Laos and its economy is starting to grow slowly.

So did you save money in Laos too?

Paradoxically, Laos is one of the most expensive countries in Southeast Asia. Transport and food are more expensive than in Thailand, and in all the interesting places for tourists you have to pay entrance fees, albeit a small, even symbolic fee, but it was obvious I was spending more money.

On the other hand I only travelled in Laos for six weeks and did not take part in any volunteer projects. I met other travellers there who agreed that Laos was surprisingly more expensive for them than Thailand. It seems to me that as China invests, prices are rising fast.

What do you remember the most from Laos?

I got high up into the mountains and to remote villages among people who may have seen a laptop for the first time in their lives and where they still live in a very traditional way. From my photos we can see that the men take care of the children and carry them on their backs. I asked about this at one museum, as I was really surprised by it, and I was told that it is more for practical reasons, because the women provide a livelihood and don’t have much time to raise their children. I also visited amazing karst areas, forests and a few interesting historical monuments.

From an ethnological point of view, Laos is a remarkably interesting country. Which ethnic groups live in Laos?

That is true. The three main ethnicities in Laos are Lao, Khmu and Hmong. The most numerous group is the Lao, after which the country is named. The Lao typically are Buddhists. On the other hand, the Khmu people are animists. I met some of these people in the Nam Ha National Park, a protected area near the city of Luang Namtha. This was one of the few trips where I was accompanied by a guide, who told me about the Khmu people: for example, how they believe in ghosts who occupy their living quarters. For this reason, the dwellings must be configured in such a way to avoid collision between the different spirits. Fascinatingly, when the Khmu people get ill and medics cannot find anything wrong, they ascribe the cause of the ‘illness’ to the ghosts.

Can you describe the dish in this photo from your ‘forest lunch’?

This was our picnic in the forest. We had soup and fried fish cooked on the campfire. You can also see a lot of greens, such as lettuce. It was a delicious meal!

We have not yet mentioned the third ethnic group, the Hmong people. Could you describe them?

Of course. This is a very large group that also lives outside Laos, for example in China, Vietnam and northern Thailand. In Laos, many Hmong took part in the resistance against the Communist-nationalist ruling party and had to emigrate. Some formed a large community in the United States.

What I’ve described is a very basic description of Laos’s ethnic groups. In talking with local museum staff I learned that the ethnic division is far more complex in terms of languages, and really we should talk about a fourth group too, which includes the Akha tribe, who are also found in other countries such as Thailand.

Did you get to the waterfalls on the Bolaven Plateau?

Yes, this is a plateau in the south of Laos where you’ll find the beautiful Tad Fane waterfalls, about 120 metres high. These, along with another waterfall in Laos called Kuang Si, are probably the most beautiful waterfalls I have ever seen.

What was your next stop after Laos?

I travelled to Vietnam.

What did you think of Vietnam when you arrived?

At first I found it very chaotic. I must admit that I didn’t like it as much as I thought I would… Of course, there were a few places that were absolutely amazing! I felt this way because I’m a calm person and sometimes I went a bit nuts in Hanoi, although it has real charm. You’re surrounded by noisy motorcycles, messy traffic, hustle and bustle and everything hums and honks. To be honest, those Vietnamese megacities were the least enticing places for me from all my travels across Southeast Asia. But when I ventured outside the capital to the Vietnamese countryside, I had a great experience and saw many beautiful places.

Here’s another photo from your album called ‘People of Ha Giang’. Where is Ha Giang?

This area is located in northern Vietnam near the Chinese border and is known not only for its stunning landscapes but also for its ethnic diversity. The most numerous ethnic groups in Vietnam are the Viet and Kinh. Obviously Vietnam got its name from the Viet, even though it is only one of many ethnic groups.

In Ha Giang only 10 per cent come from the main ethnic groups and the rest of the population is mainly Hmong, Tay, Dao and Nung people. I really enjoyed my travels in Ha Giang. I rented a scooter so I could get to know the traditional life in the villages and see the breath-taking landscapes and nature.

- People of Ha Giang in Vietnam. Photo: Jan Toman

- People of Ha Giang in Vietnam. Photo: Jan Toman

From your photos it seems that people in rural parts of Vietnam still live more traditionally than in Thailand – is that true?

The people of Ha Giang are really very traditional and we can see they wear traditional clothes. However, we can meet people who live a similar way of life in Thailand, such as the people of the Akha tribe, but even there we can see a noticeable progress of modernisation. Some Akha people still build traditional huts, others are already living in modern houses.

You even became a teacher in Vietnam, by chance. How did that happen?

On my last day in Vietnam I was walking down the street, not far from the Cambodian border, and I met two young girls who spoke perfect English. I was surprised, so I praised them as they were speaking it really excellently. They explained to me that they were teachers. They offered to take me to see their language centre and said they could arrange work for me as an English teacher.

Unfortunately, my visa was running out so I couldn’t take this job, but they asked if I would like to teach one extra hour of English conversation to their students. This turned out to be a really great offer, because the language centre paid me in the form of a hotel room, dinner and even the bus ticket to Cambodia. So, for just one day I became an English teacher.

You travelled from Vietnam to Cambodia. How did you get there?

Partly by hitchhiking, partly by bus.

Is it possible to hitchhike across the border?

Yes. [Smile] I crossed borders like this several times. You can either hitchhike to the border and then cross on foot, or you can stop a car riding into the neighbouring country. So, yes, it is very easy. I hitchhiked across the border between Malaysia and Brunei. It may sound a little bit odd but I think it is definitely better to hitchhike across the border than to take a tourist bus. For example, I heard that the Thai-Cambodian border is a ‘trap’ for tourists. The bus takes them somewhere where they have to pay 20 dollars more for a visa than it should really cost, and they can’t get out of it.

In Vietnam, the hitchhiking was a bit tricky because there is no term for it in Vietnamese and people absolutely don’t understand what is going on! [Smile] When you try to stop a car, people tend to think that you are looking for a taxi or they want to offer you a taxi service with really high charges! I found out from the hitch-wiki page that one should make a sign with the words ‘Xi Xe Mien Phi’, which means, ‘Would you take me to [add placename] for free?’ However, I preferred to travel by bus in Vietnam because there were some really long distances involved.

What do you think are the biggest differences between Vietnam and Cambodia?

Overall, Cambodia is a slightly poorer country than Vietnam and is not so strictly Communist at present. The big problem in Cambodia is access to education, because the brutal regime of dictator Pol Pot destroyed all intelligence and the education system in the 1970s.

From an ethnological point of view, Cambodia is a very homogenous state, like Vietnam, and 90 per cent of the population are Khmer people, who are Buddhists. In some areas there are a few animists. By contrast, Vietnam has among the highest number of people in the world who do not follow any religion.

In Cambodia, as in Vietnam, everything is divided into tourist and non-tourist areas. Naturally, I preferred the non-tourist and wilder areas. For example, I went to the Cardamom Mountains, where there is jungle, although even there I saw how deforestation is progressing. In some places every tree by the roadside bears a sign prohibiting chainsaw use by law, with threat of imprisonment, but even though I saw a lot of rangers on motorcycles – some even with guns – I also saw and heard the chainsaws and deforested areas. Unfortunately, that is the reality in the Cardamom Mountains.

What other interesting places did you visit?

I also visit Siem Reap and saw one of the most famous historical monuments, Angkor Wat, the legendary temple complex. I also visited the floating village of Kampong Phluk on Tonle Sap Lake.

You visited a Cambodian primary school founded by Veronika Pospisilova, another graduate in Ethnology from Charles University. Tell me about your experiences there.

I took this trip on my last day in Cambodia before returning to Thailand. Veronika Pospisilova gave me instructions in how to find it. The village is so small that it’s not on any map, so it was especially useful to get these details from Veronika.

What really surprised me was the fact that this village, called Bantayrersey, is located between two extremely popular tourist destinations – between the temple Angkor Wat and the floating village of Kampong Phluk. I was surprised because the locals weren’t used to seeing tourists or even any Europeans! So it’s quite strange that just next to the main highway to Kampong Phluk, which is used by hundreds of tourists every day, there could be such a remote village, where children have to work hard in the fields and they had not have a school.

Making the journey to this school could be quite a difficult endeavour because its name is very similar to another village near Angkor Wat. I was holding a big piece of paper with the name of Bantayrersey written on it, but people thought I was going to the temple. So everyone told me I was going the wrong way and should go back! [Smile] They couldn’t understand at all why a tourist from a Western country wanted to visit a poor Cambodian village and its primary school! It made no sense for local people and it took me a long time to explain. After a while, with the proper spelling and when I showed the crayons I had for the children, they understood with astonishment. I even travelled the last 2 kilometres with a policeman on his motorcycle.

- A Cambodian school in the village of Bantayrersey, founded on the initiative of an ethnologist, Veronika Pospisilova. Photo: Jan Toman

It was a great experience for me to see exactly what Veronika had established there. I saw how the school worked, its daily routine, what subjects the were children learning and I enjoyed the happiness my little gift gave them. However, I also witnessed poverty and also children begging.

Did you get to Burma (Myanmar) too? I ask because I can see the people of Burma in your photos.

No, I wasn’t in Burma, this was in Malaysia. I travelled there after visiting Cambodia and spending another month in Thailand. In Malaysia you have the advantage of getting a 90-day visa for free, so I was able to enjoy several volunteer projects there. I had an amazing experience with the Karen ethnic group, whom I stayed with for a whole month. Karen people are a minority ethnic group in Burma, but they also live in northern Thailand.

Did you meet Karen people near another organic farm or somewhere else?

Yes, it was on a farm which was founded by two Malaysian officials. Even in Southeast Asia, establishing ecological farms is quite popular and an alternative way of living. These two men set up their farm in a place where coal used to be mined, then there was a field where they grow flowers for the Hindu temple (as there is also a relatively large minority of Hindus), so these two Malaysians are trying to develop a permaculture economy. They employ Karen people as well.

In Burma, Karen people experienced a long and long bloody civil war, so many of them escaped to neighbouring countries. The Karen family who were helping on this farm also had run away from civil war. Some Karen tribes are well known for their ‘long-neck’ women.

How did this family welcome you on the farm?

It was such a warm welcome! They literally accepted me as their own into the family. Their aunt even washed and cooked for me, so she was aunt to us all. It was really sweet. Interestingly, probably two-thirds of Karen people are Buddhists and one-thirds are Christians. This larger family was Christian.

Other Karen Christian families live around this farm and they have established their own community, built their own church from a house and they take prayers there. This church also served as a temporary asylum for Karen refugees.

- Mr. Simon one of the founders of an organic farm in Malaysia. Photo: Jan Toman

- Karen little girl in Malaysia. Photo: Jan Toman

Was Karen Christianity influenced by Buddhism in any way?

I would say no, because they are an ethnic group that converted to Christianity a long time, and so they practise the religion in its purest form. Perhaps [you can see the influence of Buddhism] only in the way they pray, as they sit in a circle in the so-called ‘lotus’ position.

What did you like about Malaysia?

I liked the way – and I said this in my speech during the introduction to a religious service when I was staying between Karens – that Malaysia is a very tolerant country and people live peacefully there: Christians, Muslims, Buddhists and Hindus, side by side.

This is also caused by the fact that Malaysia is made up of 50 per cent Malayan Muslims, and there are also Chinese and Tamils (Indians), and together these groups make up the majority of the population.

In addition, there is a small minority of Filipinos or the autochthonic original inhabitants of the Malay Peninsula, who are also referred to as the Orang Asli. Interestingly, some Chinese, who were traditionally Buddhists or Christians, are converting to Islam or Hinduism as well. Perhaps they are choosing Islam due to fact that they must if they want to marry a Muslim woman.

If you were to summarise your impressions from your travels across Southeast Asia, what would they be? What was your idea of Asia before and after your trip?

To be honest, in each country I witnessed little difference from what I expected. On the whole, I would say that in the more commercial areas, people are not so opened than I thought. In Thailand, I was surprised that the locals could not speak English very well, even though Thailand is a more developed country with a huge tourism sector compared with its neighbours.

Lots of people told me that in Laos no one speaks English at all, but in fact their understanding of English was at least comparable to in Thailand.

In Vietnam, I didn’t expect that some places would be as commercial as they were. And I was pleasantly surprised by the people in Cambodia. I’d heard myths about how ruthless people in Cambodia are but I didn’t find that to be true at all. Cambodians are very kind, friendly and warm people and they can even speak English! I was also surprised by the availability of Wi-Fi and ATMs in Laos and Cambodia. This was probably the biggest ‘Wow’ – how the Asians are skillful in technology.

I didn’t expect Malaysia to be so heavily Muslim. I also remember a very funny moment when two Malaysian people were confused by the name ‘Czechia’ and they thought it was ‘Chechnya’. However, many Malaysians have a connection with the Czech Republic through the football goalkeeper Petr Čech, and even people who don’t speak much English immediately think of him when they hear ‘Czech Republic’. They love watching British football, the Premier League, even though Malaysia do not excel at football – their main sport is badminton.

What Southeast Asian country would you love to visit again?

I would say Cambodia. I liked the overall atmosphere of the country the most out of all the countries I visited. I would like to travel around it more, as I didn’t have much time to explore it all.

Do you think that there is any significant difference in the way of thinking between Czechs and Asians? And is there anything we can learn from?

The way of thinking? I don’t think you can generalise like that. I would say there is a slight difference between the Thais and Laotians, and the Vietnamese. Overall, people perceive time a little differently. They are not bothered by being right on time. For example, when I waited about an hour longer for the bus in Cambodia, they said to me “Sorry, Cambodian time”, with smiling faces. They also have a completely different attitude towards money and saving. In Thailand, Laos and North Vietnam, local people didn’t understand why I was hitchhiking, or why I preferred to sleep out in the open when I had the money for a hostel.

In whole you need help or advice, there are two group of people: those who are extremely kind and willing, and those who do not give a damn. I also noticed that some people prefer to ride a motorbike for a distance as short as 50 metres and if you ask how far away a place is, they reply ‘very far’ even it it’s only one kilometre. [Smile]

We should definitely learn from Asians in the way they hold their families together. I would also say that Asians, unlike Czechs, approach everything with positive optimism.

What do you think people in Southeast Asia could change or improve?

What they definitely need to improve is ecology and their attitude to the environment. For example, the amount of plastics that Asian people use and the waste they produce is absolutely alarming. According to some figures, up to 90 per cent of all waste entering the oceans comes from only 10 rivers in Africa and Asia. One of these rivers is the Mekong, which flows through Southeast Asia.

When I volunteered in Cambodia at a mangrove river resort, I tried to clear up as much garbage from the mangroves as possible, but as soon as there’s a storm and rain, the river carries in more garbage. Education represents hope but the problem is that in Cambodia many children do not even have access to a basic education. From my point of view, it is necessary to implement subjects such as environmental education in schools so that the future generations gain some awareness of the environment.

For people who can study, they usually choose more technical disciplines. Environmental management as a study programme does exist in Malaysia and I even spoke with one female graduate. However, she confirmed that there is not much interest in such fields in Malaysia, because they do not make that much money.

For example, Malaysia is one of the countries with the largest biodiversity in the world. However, the primary rainforests – jewels of natural diversity – are disappearing rapidly and most of them are being replaced by palm oil plantations, which are said to have a lower biodiversity than the spruce monocultures of Europe.

Although I like Malaysia very much, I was often very sad when I was driving through areas where a few years ago there was a rich and dense tropical forest and now there is palm oil plantation.

Southeast Asia is dynamic and so is developing very fast. Sometimes I even felt that I simply arrived there ‘too late’ as the traditional atmosphere has gone from some places, but still it prevails in other areas. As I’ve said, in addition to all the negatives, there are also people with awareness of the problems who come up with alternative and more sustainable ways of farming and living. And I was so happy and excited that I could take part in these ecological projects, helping as a volunteer, and I saw many places where wild nature still thrives.

Interesting links:

Cestovatelský blog Jana Tomana

Friends of the Asian Elephant (The World´s First Elephant Hospital)

Nam Ha national protected Area (NPA)

Terrawatch: the rivers taking plastic to the oceans (The Guardian)

The Radical Conservation of Cambodia´s Most Mysterious Rain Forest