Milan Jeglik: I left my soul in Sumatra so that I could find my heart in Costa Rica

Milan Jeglík is one of the most important Czech conservationists. Although he was born in the Moravian city of Brno, you will have a better chance of meeting him in the rainforests of Sumatra, where he buys land to prevent illegal logging and further growth of the palm oil industry. In Sumatra, he has managed to buy a large area of rainforest, where he has also founded the anti-poaching ‘Green Patrol’, led by the ‘Tiger command’, which his colleague Zbyněk Hrábek is part of. When Milan is not in Sumatra, he is negotiating new terms with the Costa Rican authorities for a unique project, ‘Green and Blue Life, Costa Rica’ to protect the marine world, which is still very fragile despite government measures to protect it. The list of Milan Jeglík’s activities does not end there. Other ongoing conservation programmes which he founded with his partner Zuzana Koloušková include the ‘Eye of the Earth’ project, which will monitor endangered species from four continents for five years and will detect illegal activities by poachers and miners in cooperation with the International Ranger Federation. He also invests his energy in the education of the Czech and Slovak public, delivering lectures about his conservation fieldwork. He believes that only the general public can stop the deforestation of primary forests and he hopes that the next generation will be more informed about their importance. That’s why he and his team founded an educational programme in the Czech Republic.

Milan, your life today is more like something from an Indiana Jones movie, except that you save rainforests and endangered animals rather than ancient artefacts. You regularly stay for half a year in the field, where you negotiate the purchasing of Indonesian land, and the other half of the year you are lecturing in the Czech and Slovak Republics. Where does your desire to protect the Indonesian rainforests come from? And what was your original profession?

I was lucky enough to take an important decision when in 2002 I was working as a policeman but travelled to Indonesia to be a diving instructor. It was a turning point in my life. As well as diving there, I gradually discovered illegal fishing practices and looked behind the scenes. I have seen people who kill sharks, dolphins, manta rays and even whales. This changed my life a lot and I started thinking more deeply about humans and I started to ask: who are we – humans – really?

In 2004 I visited Sumatra for the first time and the rainforest literally took my soul. In 2006, together with other Czechs, we opened our own diving centre on the island of Nusa Penida near Bali and every two years I sailed with the diving expedition on a ship called Sea Lady to the Indo-Pacific Ocean. Then, I decided to end my commercial diving and to protect endangered species, such as tigers and orangutans, in Sumatra. I started to purchase the first piece of rainforest land in 2009 and founded the ‘Green Life’ project to protect the rainforest. And yes, my original job was police officer, but I am glad I decided to travel to Indonesia in 2002 – I couldn’t do that job today.

Did you have a deep connection with nature and animals from a young age?

I was very lucky that I have great parents. In particular, my father devoted a lot of time to walking in nature with me. I have been going to the forest with him since I was a child, we camped and wandered as a whole family and I gradually understood that nature is not dangerous but rather an immense source of experiences, and more importantly adventure, for a little boy. So, as a child, I was more the outdoors type, running around outside, rather than staying indoors or in the city.

I am also grateful that we did not go to the zoo or circus, that we did not have any animals in captivity (except a stray cat or dog), and thanks to this I was able to cultivate a real relationship with animals and understand how important their freedom and natural habitat is. I consider this to be an especially important foundation bestowed on me by my parents.

What took you to Sumatra?

I was brought to Sumatra by my desire for an adventure, and especially for learning about the rainforest. It is a completely different forest than we have in Central Europe. The tropical rainforest is real, perfect and most importantly, unmanaged by people.

My first experience with the rainforest was in Gunung Leuser National Park. When you have the opportunity to see how ancient and huge the trees are there, watch the orangutans or follow in the footsteps of a tiger, it completely changes your view of the world. You see a space where animals live freely. When I saw orangutans in the Czech zoo in Usti nad Labem a few years ago, when I was filming a documentary about the suffering of animals in captivity, I welled up with tears and felt a deep sense of sadness, anger and despair. I find it incredibly sad to see any animal in captivity.

What created the turning point for you in 2009? Why did you decide then to move away from your secure and lucrative job as a diving instructor to the challenging life of a conservationist?

To be honest, I was fed up. I could see no progress or future. I wanted to continue more ethically and less commercially, but my companions in the diving company were not on the same page. I wanted to spend part of the year monitoring the coral reefs and sailing along the coast, teaching fishermen why they should not be using explosives, but I didn’t get a chance to change the direction of the business, so I let it go. In the end I made the best choice I could, and together with my girlfriend founded the ‘Green Life’ project in Sumatra, which is working successfully to this day under the leadership of my colleague Zbyněk Hrábek, who has lived in Indonesia since 2016.

The association ‘Justice for Nature’ was founded in 2009 to save the rainforest.

Can you describe in more detail the situation and practices of illegal hunting of wild animals in Sumatra at that time?

Every time we went on patrol in the jungle, including Gunung Leuser National Park, we found dozens of poaching meshes. Nobody cared, not even the rangers. Nutcrackers and porcupines disappeared from the entire area, and although we destroyed poachers’ bird traps, we felt it would never end or that someone would confront us.

Finally, we managed to reduce the poaching and we bought more and more land in the rainforest and employed men for our anti-poaching ‘Green Patrol’. Today, I can genuinely say that we have achieved great success in reducing poaching in our area. However, this doesn’t mean that poaching has completely disappeared, but our reservation is clear of it and even tigers pass through, and orangutans appear regularly. In 2018, some elephants visited our reservation. We could see from the photo-traps that animals that don’t usually live in our area were coming.

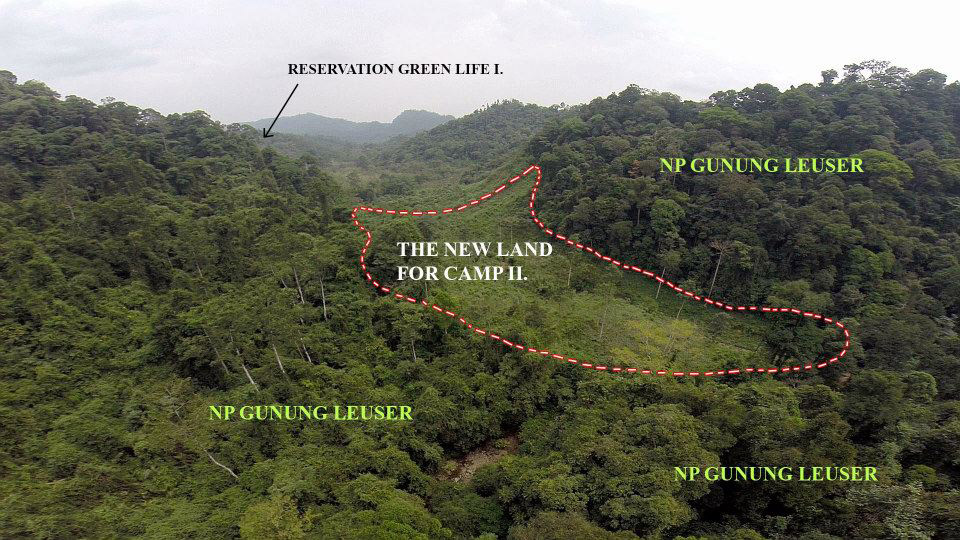

You founded a non-profit organisation called ‘Forest for Children’, of which you are the chairman. It’s focusing on the purchase of land in the border zones around Gunung Leuser National Park in northern Sumatra, to make it more difficult for poachers to penetrate the rainforest. What has the organisation achieved since 2009 and how many hectares of land around the National Park does it own now?

We focused on one specific area in the Bohorok district, which is an extremely interesting area inhabited by Sumatran tigers. We gradually bought land contiguously and today we have 175.5 ha of land directly bordering the park. It’s not much, but it’s a great benefit as it prevents poaching in the tiger area. Today, our anti-poaching team has four field camps available, which we also use for volunteer programmes.

In 2015, we built the base and the main headquarters called ‘Tiger House’, which represents our activities in Sumatra. Currently, we are negotiating the purchase of another five hectares of land. Actually, it’s a never-ending story but a beautiful one, which thousands of Czech and Slovaks are involved in and have contributed to. Our team is also committed to helping farmers prevent conflicts with tigers, so we build pens that work very well for cows. And this is all thanks to the great job performed by our team.

What I find incredible is that former poachers are also joining your organisation. This must give you a lot of satisfaction.

Yes, this is one of our important programmes, a rehabilitation programme for former poachers who have decided to give up their current activities and join us. It works! You know, everyone should have the chance to put things right, and if he accepts the challenge he should be given the opportunity to do better things. It is important not to waste this chance and this applies to all of us and our lives, not just poachers.

- The Czech NGO Justice for Nature works closely with the International Ranger Federation.

- Czech Zbyněk Hrábek leads the anti-poaching ‘Green Patrol’ in Indonesia.

- The World Ranger Day falls on the last day of July. Photo: Organization YHUA

What has the Covid-19 pandemic meant for Justice for Nature? Did you have to postpone your fieldwork?

For all nature conservation field projects, this pandemic has been literally a deadly period. For us, it means we have already lost two three-month volunteer programmes, which were fully booked, and it looks that we could lose the third season this summer as well. This is a loss of more than a million Czech crowns for our project, which no government will compensate us for.

The Blue Life project has been limited only in Sumatra, but otherwise fortunately everything is going really well and there are many people who have really supported our activities. We are also running a brand-new conservation project in Costa Rica, so we are extremely excited!

In this short documentary, you can find out what it like to be a volunteer in the Blue Life programme in Sumatra.

How do the local people view the rapid decline of the rainforests? Does the Forest for Children project also get support from the locals?

Modern Indonesians still do not deal effectively with deforestation much, nor can they, because often they do not know the context and also, working on palm plantations or poaching could be their only livelihood. However, I know several activists who are very active. Unfortunately, some of them are no longer alive because they were killed by murderers hired by multinational corporations, for example palm oil companies or Chinese development companies building dams. It’s a desperate situation, but we can’t close our eyes to it.

Rainforests deserve our attention and need to be protected despite the clear risks that our work in the field could create. As for the locals, I’d say there are three groups: those who do not solve us; those who cooperate with us; and then those who essentially hate us, and these are mostly poachers or corrupt officials. That’s just life.

How is it possible that, despite media campaigns by the world’s leading environmental organisations and their public financial support, rainforests (not only in Indonesia) are still declining, at an enormous rate? What do you see as the biggest problem in nature protection?

Well, if the biggest environmental organisations used their money to buy land in rainforests, they would do better. If every non-profit organisation saved 200 or more acres of rainforest and gave people jobs in anti-poaching patrols, there would be a concrete result.

Why are rainforests declining so rapidly? Because the public literally consumes them: in tropical wood, palm oil, rubber or eucalyptus. Obviously, campaigns don’t work as they should. There should be [more] teaching in schools about the problems faced by the rainforests and more energy should be put into spreading global awareness in the mainstream news regularly. We must realise that it is because of industrial commodities that forests are burned, logged and destroyed. For example, take a look at what oil is used by the biggest fast-food chains, the ones people visit so often. They may tell you that they use certified ‘sustainable’ palm oil, but in reality it is just business with certificates. This whole would-be ‘green business’ is one big scam in my eyes. When I see NGOs calling for the use of certified palm oil, which WWF is also signed up to, I feel truly sick. The reality is that rainforests will disappear, and along with them the elephants, tigers and orangutans, unless people become really interested in their preservation and unless national governments and the international community address this more effectively. For instance, they could impose a trade embargo on countries that do not comply with international ecological agreements. Indonesia is just one such country.

To sum up, the biggest problems are corrupt state administration, human consumption and a very poor education system about ecology, especially from the media.

Do you think that ecotourism will significantly help with conservation work and promotion of national parks? To what extent do you collaborate with people who would like to visit certain places in the rainforest in Indonesia?

In many areas, ecotourism is the only reasonable income for local communities, so it allows them to exist without carrying out illegal activities in protected areas. Proper ecotourism also educates visitors about the importance of nature conservation. Unfortunately, Covid-19 completely destroyed ecotourism and drove many people back to illegal poaching activities, and this is really bad.

As for our project activities, we do not run ecotourism, only volunteering and educational programmes, which I call the ‘holiday of the 21st century’. Being a volunteer lets you see lots of interesting places, but also involves you in conservation work, which helps you understand things in context. From my point of view, classic tourism is actually just another form of consumption. Volunteering is more progressive. It’s the way of the future.

Tell me about your other project, The Eye of the Earth. What is it focused on?

The Eye of the Earth is a global project monitoring wild animals using photo traps. The uniqueness of this project lies in the fact that our main partners are primary school students, whose parents and teachers support us by raising funds to buy more photo traps. We have used these on several continents for animal monitoring and research, and to detect poaching.

So we’ve been able to involve children in this nature conservation project and as a reward, they receive unique shots from the photo traps. Otherwise, this project focuses mainly on critically endangered species, especially predators. The main output will be an international educational programme called Ethics of the Earth, based on recordings from the photo traps around the world.

You are also working in Costa Rica, where, among other things, The Eye of the Jaguar project is taking place. What is that about?

The Jaguar’s Eye project focuses on monitoring the largest feline predator in the Americas. We’re working closely with Leonel Alonso Delgado Pereira, President of the International Ranger Federation for Central America, who has opened the gates to this beautiful country, where animal hunting and animal circuses are banned, and most zoos have been closed.1.In 2013, Minister of the Environment René Castro submitted a proposal to close all zoos in Costa Rica and return animals to the wild or reservations. Since then, some zoos have been closed down and the country plans to shut the remaining two zoos, which are owned by the non-profit organisation FUNDAZOO and whose operating licences expire by 2024 under a very limited regime. The plan is to transform the Simon Bolivar Zoo in the capital San José into a botanical garden because the conditions for the animals were unsatisfactory.

We are also working closely with scientists from a non-profit organisation called NAMÁ, who have been studying and monitoring jaguars for 12 years. This is a truly amazing team of people who have already had many years of practice in conservation work in the field and outstanding results. Our monitoring takes place in the Corcovado, Santa Rosa and Guanacaste National Parks. We have the first two highly successful monitoring months behind us, which led us to the idea of opening another branch of our organisation Justice for Nature in Costa Rica. We are putting extra energy into our project activities there. I truly hope that in the next few months there will be a Green Life Reservation at Tapanti National Park.

Costa Rica is known among travellers as the ‘green jewel’ of Central America. The country is unique not only for its rainforests, exotic animals and beautiful Caribbean beaches, but as you mentioned, it is Central America’s green leader in terms of its progressive wildlife and nature conservations laws.

In 2013 the media reported that the Minister of the Costa Rican Environment, René Castro, planned to close the country’s zoos and return the animals to the wild and reservations. Costa Rica was also the first country in Latin America to ban wildlife hunting for entertainment, to better protect endangered species. How come Costa Rica is such a progressive country?

That’s exactly what I asked one very enlightened man in Costa Rica, José Roberto. He told me: “It’s taken 40 years of educating people about nature and animals.” And that is the essence of Costa Rican society.

When you see parents with children standing in queues at the entrance to a zoo and teachers with them to experience animals in captivity, I ask myself: “Can’t you see it? Can’t you feel that these animals are suffering?” Some countries already teach about empathy in school, which has led children to understand each other, and I mean not only humans, but also other living beings. I think this is really remarkable.

On the other hand, when I remember how children in schools where I gave lectures about nature and wildlife told me that it is better for animals to be in cages than in danger in the wild, I realised the desperate state of education about nature and animals in the Czech Republic.

From my point of view, all of this is based on the concepts of zoos – children are learning from early on that captivity is a form of protection, that a cage is safe and that wild animals are dangerous.

Although Costa Rica protects against the illegal capture of animals by law, are there any nature-related and environmental issues that the country faces? Why did you start the project in Costa Rica? Was it do with the fact that the country is in favour of protecting nature and that conditions are good there for negotiating with local authorities?

Although Costa Rica has well-defined laws, illegal activities take place here all the same. The difference is that game hunting is a crime here, while in contrast, in the Czech Republic, it is legal. However, despite the ban, illegal hunting is happening and the closer you are to Panama or Nicaragua, the more complicated this issue is. The Corcovado National Park has a problem with gold miners and poachers, despite the fact that it is the most famous national park in Costa Rica. Also, snakes and birds are still hunted illegally. In many places, mass tourism is also a threat to wilderness areas. Nevertheless, Costa Rica is an outstanding example of nature conservation.

As for the reasons why we chose Costa Rica for running our project activities, it is home to 4% of the world’s land-based biodiversity and 5% of its ocean biodiversity, so it is a global natural gem. While the laws apply really well on the land, the ocean has not been monitored effectively.

For example, wealthy tourists come to Costa Rica for sport fishing, which is a meaningless act of trophy hunting. Most tourists eat seafood and do not realise that they are destroying Costa Rican ocean biodiversity. There is also a huge problem with illegal fishing in Costa Rican waters, where Chinese boats operate illegally and fish sharks for the much sought-after shark fin soup. The Costa Rican government does not have ships to monitor this. Turtle eggs are stolen from Costa Rican beaches too, so for all these reasons we would like to help this country. In addition, we were asked officially it we would like to open our branch here and we certainly did not refuse the offer.

In Costa Rica, among other things, you are also negotiating the purchase of a boat that should serve as the first educational centre at sea, called The Ocean School for Central America. Can you describe this project some more?

In Costa Rica we decided to buy a boat that could be transformed into an ocean school for children and at the same time be used for scientific research and to educate about the ocean along Costa Rica’s Pacific coast. However, after inspecting boats in the port of Puntarenas we found that they weren’t in good condition and would demand a lot of work and reconstruction – so there would be more financial costs and uncertain results.

We were then contacted by former Sea Shepherd Director for Central America, Jorge Serendero, who offered us a collaboration with him and his organisation, For the Oceans Foundation, which is based in Costa Rica.2.The cooperation between Justice for Nature and For the Oceans Foundation officially started on 30 July 2021 in the Palo Verde National Park on the occasion of World Ranger Day. We decided to go ahead and started to prepare a plan and cooperation agreement for a new, unique project called Ambassadors for the Oceans. In June 2021 we learned that the organisation Ocean Voyagers would provide us with a stunning 45-metre-long ship as the partner of the Ambassadors for the Oceans project. We also got the attention of Monaco’s Prince Albert II.

If everything goes to plan, the Ambassadors for the Oceans project will launch its ocean mission with two ships from 2022 to conduct research, monitoring and conservation work, educational activities and media campaigns in Costa Rican waters, extending into the Pacific Ocean around Central America. Our main goal is to throw more light on illegal fishing and begin collaborating with the Costa Rican government and other important organisations to protect the unique places around the Osa Peninsula, Cocos Island and the Thermal Dome.

Another of our missions will be an international educational online programme broadcast via satellite not only to the countries of Central America but to the whole world. Another important task will be to clean discarded floating fishing nets known as ‘ghosts nets’ out of the ocean. These are literally killer traps for ocean life. I am sure this will be tough and dangerous work, but it will be very beneficial. International volunteers will be involved, whom we rely on a lot. Our new website, Ambassadors for the oceans, will explain everything to the public. It will be a really amazing project!3.Justice for Nature’s work in the Tausito area achieved its first results at the end of July. Its first volunteer programme took place from 3rd to 23rd July, attended by seven volunteers from the Czech and Slovak Republics. The volunteer and educational centre is due for completion by the end of August 2021.

- The Czech project Blue Life Costa Rica will soon start its research activities.

- Milan Jeglík’s project promises to involve the general public in support of the protection of the underwater world.

- Photo: Zuzana Koloušková, Monika Jeglíková. á

How was this idea born?

The idea itself was born at the end of January this year on Caňo Island, where we dived with rangers and filmed underwater for a week. When I found out that the Costa Rican rangers did not have basic diving equipment, including bottles and compressors, I thought we would help them. One evening I sat down at the computer and discovered one interesting boat for sale and more or less told our sponsor my intention and he said yes! It was faster than I expected, and the secret dream became a great vision that we are working on at the moment. However, the first selected ship did not pass our requirements, so we are looking for another. We are considering one that is worth $670,000, so we still have a lot of fundraising to do. By the end of 2021, everything should be ready to start and the Thermal Dome will receive the attention and protection it deserves. I also believe that the idea for the first floating school in Central America, The Ocean School, will be a great global example of international cooperation to protect the underwater world and educate children about the ocean in Costa Rica.

Are many volunteers from Czech Republic or Slovakia interested in volunteering in Costa Rica or Indonesia?

These days, there are groups of volunteers who want to participate in our projects. However, we do not intend to open volunteer programmes in Costa Rica until July 2021, at least we hope so, as we will need help with the completion of the forest camp and repairs.

Needless to say, you have witnessed the devastation of nature firsthand. I can see the seriousness of the situation, but also how an ecologist can be depressed by the rate of deforestation. What motivates you and gives you optimism? Do you see any major shift in the perception of the importance of the ecosystem by local people, whether in Indonesia or Costa Rica?

Indeed, I feel positively charged by nature and so I do not let myself be depressed unnecessarily by human society, and especially not by negativity in the mass media. You know, if a person acknowledges the true state of nature and submits to modern ecological alarmism, then he could feel so depressed that he wouldn’t have any energy to change anything. What I do fulfils me, I believe in our project journey and I have a strong sympathy with people who perceive nature and animals as something which must be protected.

Milan, if you were to summarise your work and experience in the protection of nature, what would you say? What is your most memorable experience?

The deepest experience I had was during the talks I gave at the Czech primary school, when a six-year-old boy brought me 10 CZK. He told me that it was for his first square metre of Indonesian rainforest. I must admit that tears welled up in my eyes at that moment.

But you probably mean experiences in the wilderness. It would take a long time to describe those! [Smile] I certainly won’t forget meeting a tiger, a jaguar and a gorilla face to face, or placing a photo trap next to the dead body of a buffalo in the tall grasses where the lions were, but we didn’t see them. It was a really great adventure! I also like to remember the encounter with the Sumatran elephants in the jungle and preparing a short documentary about grizzly bears in Alaska.

My deep passion is diving, so encountering a humpback whale or hammerhead sharks – I adore these sea creatures – was truly amazing! What more could I say? Nature is absolutely magical, and it brings you unforgettable experiences that no one can take away from you.

What would you say to people who are thinking about getting involved in your projects? What kind of volunteers are you currently looking for?

Don’t hesitate to get involved because you are very important on this journey. Look at our Justice for Nature website or just watch some great documentaries, such as the new Seaspiracy movie about the fishing industry, and then try to think about what you are buying and consuming.

The new documentary film ‘Seaspiracy’ (2021) focuses on the impacts of the fishing industry and the problems of trawlers. The film not only documents the current state of the oceans, but also reveals the support of various interest groups, non-profit organisations, and also governments. According to the young British documentary filmmaker Ali Tabrizi, the oceans and seas could be empty if we do not significantly reduce our fish consumption. The Netflix streaming documentary was remarkably well received – although Tabrizi faced significant criticism from representatives of fishing companies.

We will be glad to see you on any of our projects, whether in Sumatra, Costa Rica or Slovakia, you are welcome everywhere! As for the type of volunteers, in Costa Rica above all we need skilled mechanics, welders, electricians, plumbers… So, people who are happy to work hard.

In Slovakia we need people who are not afraid to go out into the wild, active people who like hiking and who would like to help with monitoring illegal hunting activity. In the Czech Republic we need help with detecting illegally poisoned animals, and in Sumatra it’s about working in the rainforest and cleaning up plastic from beaches. There is no place where we don’t need volunteers and their help. Even sharing our project activities is a great way to help our non-profit organisation.

- Milan Jeglík also initiated the foundation of civil patrols in the Czech Republic to detect the illegal use of poison in the natural environment, especially carbofuran and Stutox II. Photo: Zuzana Koloušková

- Justice for Nature volunteer projects, also taking place in Slovakia. Photo: Milan Jeglík

How can a person who cannot travel abroad because of his work, for example, get involved? Can he become a sponsor?

Yes, this is a problem for many great people. Some of them have a job, family or pets which means they cannot stay abroad for long. In those cases, we offer a nearest volunteer programme for Czechs in Slovakia. The Slovakian volunteer projects are amazing but at the same time just short programmes. People can learn about nature in the field and if they are lucky enough see some carnivores such as the brown bear.

Otherwise, of course, people can support us financially, professionally or through the media. They can save a piece of rainforest, buy some gifts from our e-shop, or support anti-poaching patrols. All the information is on our website.

Milan, thank you very much for the interview and I wish you all the best!

Me too and thank you for the opportunity to show people our project activities.

| ↑1 | In 2013, Minister of the Environment René Castro submitted a proposal to close all zoos in Costa Rica and return animals to the wild or reservations. Since then, some zoos have been closed down and the country plans to shut the remaining two zoos, which are owned by the non-profit organisation FUNDAZOO and whose operating licences expire by 2024 under a very limited regime. The plan is to transform the Simon Bolivar Zoo in the capital San José into a botanical garden because the conditions for the animals were unsatisfactory. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The cooperation between Justice for Nature and For the Oceans Foundation officially started on 30 July 2021 in the Palo Verde National Park on the occasion of World Ranger Day. |

| ↑3 | Justice for Nature’s work in the Tausito area achieved its first results at the end of July. Its first volunteer programme took place from 3rd to 23rd July, attended by seven volunteers from the Czech and Slovak Republics. The volunteer and educational centre is due for completion by the end of August 2021. |