MA Stanislav Lhota, PhD.

Stanislav Lhota is a Czech primatologist, zoologist and conservationist of Indonesian environment. He works in the Usti nad Labem Zoo and at the Faculty of Agrobiology, Food and Natural Resources at the Czech University of Life Sciences in Prague. He is an active member of the Czech Coalition Against Palm Oil and he is an opponent of palm oil and oil palm plantations, which currently cause deforestation and the burning of rainforests on Borneo, the rapid retreat of diverse animal life forms and also the deteriorating living conditions of people in Indonesia.

Stanislav Lhota also contributed, as a scientist, to the documentary ´Green Desert´ from Slovak director Michael Galik, who carefully documented the situation on Borneo and the horrific practices of companies planting oil palms, like the burning of rainforests with the native animals, discharging orangutans and confiscating the land of residents who live in areas where oil palm plantations are. Furthermore, Stanislav Lhota speaks Indonesian fluently and he is the author of a number of Czech and English studies and also popular articles about his conservation field work and experiences in Indonesia.

Mr. Stanislav Lhota, my first question will be, why did you choose zoology, specifically primatology? What circumstances led you to study this field?

Actually, I have been studying zoology since my childhood and I was really interested in the psychology and cognitive abilities of animals. For this reason, primates appealed to me because for them is typical to have a lot of cognitive abilities and also in terms of comparative psychology it is a very interesting area. When I was studying in high school it was the time before the Velvet Revolution so there weren´t many opportunities for me to explore primates. After the Velvet Revolution I had more opportunities and I went to India. In India I worked on a Bachelor´s and also Master´s thesis about the Gray Langur. Over the years I diverged from the psychology of the animals to social behaviour, then to ecology and finally I started with animal protection issues.

About you it is also known that you regularly travel to Borneo, where you are concerned with (in addition to studying primates) environmental protection and protecting the remaining part of the forest and their animal species. When did you visit Borneo for the first time and for what reason?

It was 2005 and to be honest it was not planned, because I had been working in India for many years. Unfortunately we did not obtain a permit for futher research.

Can I ask why?

Simply for bureaucratic reasons. So, I needed to find another locality, where I could continue with my research of the Gray langur and where we could receive permission to research. Finally, we decided on Indonesia.

How were you affected by Indonesia and the local people?

Totally fine, because I spent several years in India. Particularly in India when I began with my research I was 19 years old and at this time it was a huge culture shock and for me Indian culture was completely different. In contrast I did not experience culture shock in Indonesia and it was very easy for me. Furthermore, the Indonesia climate is better for me, due to high temperature extremes in India and in connection with alternating periods of hot days and monsoons.

I know about you that you can speak fluently in the Indonesian language. How long did you spend learning Indonesian and do you use more Indonesian than English during your field research?

If person wants to do some important work in Indonesia, Indonesian is necessary. Indonesian people cannot speak English very well, so everybody who works in the field has to learn Indonesian. On the other hand, Indonesian is one of the simplest languages to learn. I spent half a year on an Indonesian language course before I travelled to Indonesian for the first time. After two months in Indonesia I could speak very well. The circumstances forced me to speak Indonesian, because I did not have many opportunities to speak in English in Indonesia.

In the introduction I mentioned that you are against planting oil palm trees in Borneo and that you appeared in the documentary film the Green Desert. Can you explain to the readers, who so far have not heard about this documentary or problems with oil palm trees, why it is so dangerous to planting oil palm trees for for the environment, animals in the rainforest and also for people who live in the area of oil palm plantations? Why should consumers choose products without palm oil?

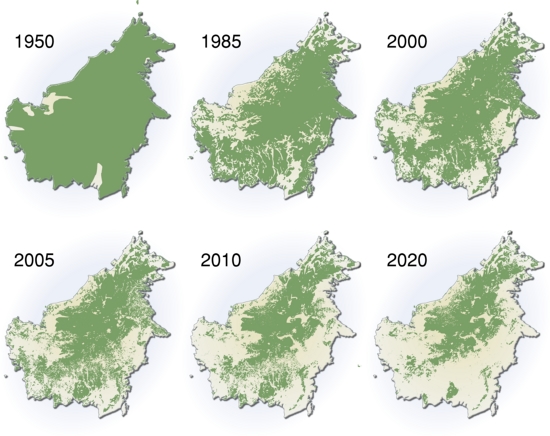

First of all, the biggest problem is of course that, the oil palm plantations are built at the expense of lowland rainforest and on a huge scale – it is millions of hectares of forest, which are constantly being converted to plantations. It is the lowland rainforest, where is the greates wealth of animal and plant species. This was the first factor.

Secondly, the expansion of oil palm trees is also running at the expense of traditional farmland so, like orangutans, many wild animals miss out on living space, local communities also miss out on living space, which has so far depended on traditional farmland and fishing. I mentioned fishing for this reason, that oil palms have a major impact on the hydrological regime of the land. The cultivation of oil palms consumes groundwater, so sometimes it causes extinction of entire rivers and simultaneously oil palms are a source of pollution. The plantations are regularly fertilized with urea, and every few months are sprayed with herbicides, and this destroys the life in the freshwater, or even near coasts in marine waters. Such as through the disappearance of traditional agriculture, as well as the impact on traditional fishing.

I have to ask you, because you might know, after many years in Indonesia, how huge area of Indonesia is covered by oil palm plantations compared to rainforests? Do you have any specific information?

It depends on the particular area and study and the specific data is different so I cannot say exactly how much it is, but accurate studies and maps by various organizations are easily accessible.

Have you ever felt a kind of helplessness or did you have any dark thoughts? To be honest, for me it was really sad to see the documentary pictures of the burning Indonesian rainforest, the rapid decline in fauna and flora and the staggering killing of magnificent animals, like orangutans, who are now for plantations and company owners only seen as vermin. These orangutans who survived the burning forests are murdered under the direct instructions and for you it must be very difficult to witness these events. Tell me how, as a primatologist and lover nature, do you cope with this situation?

Well, there is a problem in that everybody who works in the protection of the Indonesian environment has to develop some system of a certain degree of distance to preserve their motivation and interest. In my opinion, there are two main things on which it is good to focus. Firstly, there are, except for the many failures that accompany conservation work, partial successes and you simply need to remember these partial successes, and you need to constantly remind yourself of them.

Secondly, on one side there are vast tracts of rainforest disappearing, but on the other side we still have huge areas of rainforest. To conclude, it is very useful to think about what we still have and particular success stories. If you only looked at the devastation and the destruction of what you have before your eyes, after a few months or years you will give up.

Do you think, that this destruction can also lead to developing awareness of the importance of nature ecosystems of Indonesia for local people? Is it possible that it also causes the establihment of nature reservations and thus the revitalization of Indonesian fauna and flora?

Yes, definitely yes. One of the positive things that I noticed in Indonesia is the fast development of ecological awareness. Indonesian people are very well aware of the problems with their environment, they are interested in animals, the environment, but unfortunately so far relatively rarely transform this awareness into some concrete action. Most of the people in Indonesia do not have an idea or a belief that they can do away with something that they dislike and that it can somehow change. So, they are very passive. There is significant awareness and interest, but this is mainly passive and needs a lot of work in that country, indeed something must and will change.

To what extent is the Indonesian government involved in this conservation? In the documentary Zelená Púst it was said that the government is very inclined towards oil palms and its campaign in favour is lead from above.

Well, the Indonesian government has numerous programs to protect nature and this also includes establishing and managing nature reserves. On the other hand, environmental protection is held in place where there is not real danger. Very often reserves are established in places, where there are no investors who want something felled, mined or planted, and therefore nature reserves are established there. Conversely, where investor interest is somehow using or destroying resources, there is usually government support on the side of the investor. So, unfortunately, the fact that Indonesia is undergoing an extensive devastation of the rainforests and the environment is largely due to the support of the Indonesian government to investors, especially the Chinese, Russian and others.

I would like to ask you, if the nature reserve, which government has set aside is appropriate for a diverse range of natural species? I ask you, if they are in such places where it will be difficult to transport the rescued animals to, or where it will be complicated to rehabilitate them.

It depends how and where. In point of fact, the original system of nature reservations was founded in the 70s in a very random way and they were not managed effectively. Approximately twenty or thirty years ago these were only on paper, or there were a few people involved, but field work did not take place. A great part of the reservations established earlier are currently degraded and have lost all of their original value. These new reservations are often based in places where the threats are not and there is not an investor who wants to come and would like to cut down the forest. I do not say that there was no value, very often this is an area with high conservation value, but there are not the threats – that is why a reservation is set up. Nowadays, the most valuable forest areas are those where the investors are interesed in. And in these places the protection of nature is at its worst, because the support of the government is lacking.

Besides the fact that you are an active member of the Czech Coalition against palm oil, you are also one of the founding members of the new project Save Balikpapan Bay. Can you tell me what the main idea is and what the goals of this project are? And why is the area of Balikpapan Bay so unique?

Balikpapan Bay is an area where I have worked from the beginning, since 2005. This is the area on the coast of the Makassar Strait, which is so rich in mangrove forests and also coastal rainforests. Balikpapan Bay is very interesting because there still is, a fairly wide range of ecosystems, from coral reefs in the sea, through seagrasses and mangrove forests on the coast, up to the primary rainforest on the mainland. It is also one of the main centres of biodiversity and there is a number of rare and endangered animals. Probably the most important is the Proboscis Monkey. There is a relatively large population of them.

You mentioned Save Balikpapan Bay, so, it is a fundraising project that we should begin shortly in the Czech Republic (see on this page). It´s aim is to get money to support the Indonesian team who are dedicated to protecting Balikpapan Bay. This project has been running under the patronage of the Czech ZOO Usti nad Labem, called Project Pesisir Balikpapan.

When you are in Indonesia, you are always in the field, which also means long term cooperation with the local people. Can you tell me what the specific impacts of planting oil palms are to local residents? What do they think about the oil palm – as the Indonesian government calls ´the tree of life´, ecologists, on the contrary, call it ´the tree of death´?

It much depends on who you ask. There will always be a certain number of people, who will profit from planting oil palms and speak in favour of propaganda for oil palm plantations. The problem is that for every one person who benefits, this equates too many people who lose something from the production of palm oil – they are losing land and jobs. The oil palm plantation brings higher profits but on the other hand it also provides work for fewer farmers. There are a lucky few who will get well paid jobs, so they are glad, but each well paid comes at the cost of many who remain unemployed.

On the whole, the major problems are the side effects because when ground water disappears the farmers lose and they cannot irrigate their fields. When it pollutes the rivers and sea, the fishermen suffer and they have no livelihood anymore. So, the negative impact of oil palm cultivation is much much higher. To sum up, it can be said that, as a result of the cultivation of oil palms the economic and social disparities become deeper and deeper.

Indonesia is one of the most populous Muslim countries, but there are still aboriginals living there. What are the major groups of the indigenous people and how are they living alongside oil palm plantations?

There were a series of waves of migration in Indonesia. You would not find indigenous people because they are overlapped by those waves of migration. Currently, the oldest inhabitants are the Papuans on the island of Papua New Guinea or Dayak people on the island of Borneo. The original area of the Dayaks is Indochina and you can also see a wide range of Mongoloid features. After them came a whole new set of migration flows. The last wave of migration, which had quite devastating effects, was the Javanese. This was as a project of transmigration from the Indonesian government, which moved entire families from the crowded island of Java, sometimes hundreds and thousands families, to islands such as Sumatra, Borneo and Papua, which led to numerous conflicts.

When it comes to how and whom is affected by oil palm plantations, I would say that it goes through all ethnic groups. I saw Dayak tribes who oppose oil palm plantations, but equally I have met with communities of Javanese immigrants who have lived on Borneo for one or two generations. They have exactly the same problems as Dayaks. The problem really cuts through all the ethnic groups.

So, the problem of oil palm plantations is therefore a matter for the whole Muslim society of Indonesia?

Of course, after all, a substantial part of the Dayaks are Muslims and indigenous religions were mostly destroyed. Some elements of the original religion remain, but animism is illegal in Indonesia, so each Dayak has to choose from one of several religions. They mostly choose Christianity or Islam.

Among these groups, which do you have the biggest success with, in protecting rainforests and animals, and on the other hand, which groups require a greater effort?

In my opinion, is it the same as it was in the Velvet Revolution in Prague. (Smile) The most active groups are students, artists and intellectuals. These will support us and our campaigns at first. Paradoxically, the biggest problem is with the poorest farmers and fishermen who often turn for help to conservationists and they are able to run an intensive campaign, but they are very easily bribable. In this manner it is very easy for a company to come and offer some money to several key members of the community and suddenly the whole community is completely silent and withdraws from campaign. The campaign, which should help the local people, very often fails because of that fact.

How is it working with local people? I have heard that for certain ethnic groups in Indonesia, the word orangutan comes from ´man of the wood´. On the other hand, the others call orangutan ´white meat´ and it is hunted for meat or their bones go on the illegal market because it is traditionally believed that the bones are a magical medicine. There are big differences in human perception of the animal kingdom… Is this also a key factor in Indonesia?

In the language of Batak on Sumatra, orangutan is called ´džuhut butare´, which means white meat. Hunting is of course a problem, although in the case of the orangutan, the majority ethnic groups that hunted orangutans for meat caused their complete extinction, so there is one place in Sumatra where orangutans are still hunted for their meat. As everywhere else, where it was hunted for it is already extinct. Several areas remain on Borneo where Dayaks hunted orangutans for meat, but really there, where they were hunted, they no longer exist. The Orangutan is an animal that is unable to deal with hunting pressure, while they were found in a vast territory stretching from southern China, over a large part of Indonesia to Java. Most likely in connection with hunting, they are now extinct in most of these areas.

Hunting is also one of the problems that we are dealing with, not only with regard to orangutans, we are dealing with it in connection with a wide spectrum of other animals that are under threat. There is, however, a risk that if we focus too much on the issue of traditional hunting of wild animals for meat, meanwhile the corporations will continue to convert forests. And regrettably this is now happening, that some corporations financially support those environmentalists who highlight the problems of hunting and killing of animals by traditional communities. Therefore it is very difficult to find a balance in what we have to devote our time and energy to.

I would like to ask you, why is it actually advantageous for any company to burn rainforests and then plant oil palms, while the other companies are investing, at first in timber, and then turning to planting oil palms?

The cultivation of oil palms is not restricted to forest land and, so that the company could obtain permission for its cultivation it often must achieve degradation of forest land first. The ignition of rainforests is often part of this strategy – if you have a burned forest it is easier to convince the authorities that the territory has no value and therefore should be planted with oil palms.

After a long stay in Indonesia you certainly have had a lot of experience with the local culture. Have you had any really negative experiences just because you are a foreigner in Indonesia?

Oh, I have no idea… I think that Indonesia is such a cool country, but maybe I am biased because I stayed in India and Africa, where the situation is much more difficult for foreigners.

Maybe it is because you already knew Indonesian language…

Yes, this is obviously a major factor, because without Indonesian, the man in a local environment might find it fairly difficult to make contacts among the locals. In addition, Indonesians have a generally positive attitude towards foreigners and after all, we (foreigners) are often idolised by locals and they have totally distorted ideas about us – that we are all technologically advanced and wealthy. They believe that when they follow our example, they will also be very rich, happy and content, which does also help to facilitate conservation works.

And what are your positive experiences from Indonesia?

(Laughing) Now, I do not know whether I can answer this question quickly. Certainly I have had more positive experiences in Indonesia. Of course, I have to look away from the fact that I have witnessed far-reaching destruction in comparison with what takes place in Europe…

Mr. Stanislav Lhota, finally could you give me some recommendations for readers who expressed interest in your work and would like to somehow be actively involved in helping to rescue Indonesian biodiversity, in addition to avoiding palm oil? Could you also give the names of the main organizations which are working in the field and do you know whether donor funds actually come to rescue Indonesian forests and animals, and to support the local communities? Where could Czechs send donations?

Currently most organizations in the Czech Republic (of which you spoke earlier) are associated with the platform which is called CCBC (Czech Coalition for Biodiversity Conservation). On this website everyone can see what projects within CCBC are now underway. For example Save Balikpapan Bay is also one of these projects. Everyone can therefore decide which project they would like to support. On the other hand, even if financial support is of course always welcome, it should be borne in mind that the first and the easiest step that a person can do is to change their consumer behaviour. There is such devastation of the rainforests largely because the raw materials that are mined and gained there are used to produce food that we buy here in Europe.

Palm oil is actually contained in a very large number of products, which a normal consumer buys daily. Today we have the advantage that we can look on food packaging for its composition and the use of palm oil must be indicated on the packaging. So, if we avoid products with palm oil, we can fundamentally contribute to the environmental protection of Indonesia and often save money too.

So, the alpha and omega is consumer behaviour?

Yes, consumer behaviour is the most important factor. Without the pressure from consumers, any negotiations with the companies or the responsible authorities would not take place. Consumer pressure is also reflected in related conservation activities, in order to become effective.

Editorial Note: The interview between Stanislav Lhota and Barbora Sajmovicova took place on 4th September, 2015, in Prague.

Interesting links:

Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation

Environmental & social impacts of palm oil production

Palm Oil Is In Everything – And It´s Destroying Southeast Asia´s Forests