The history of the Oriental Republic of Uruguay1.República Oriental del Uruguay., situated in the south-east of Latin America, from the ethnological perspective, is largely a history of Europeans, especially the Spaniards, Portuguese and English. It is much less a history of the original inhabitants of this area, called the Charrúa who gradually disappeared with the rise of colonialism. The Europeans were fascinated by legendary fables of golden and silver cities, so they sailed across vast distances to a newly discovered continent. However, their dreams quickly vanished once they reached the region of La Plata and had to adapt to the local conditions. The fundamental change came with the Hernandarias experiment with the introduction of cattle and horses to the Uruguayan pampa. The livestock then became the main source of wealth for the gradually establishing Uruguayan nation. The transformation process from poor European immigrants to proud Uruguayans was not simple and the country experienced huge changes and trying times during the 18th and 19th centuries. It is truly incredible how the country transformed to the exemplary state in Latin America over a few years in the 19th and 20th centuries, offering extensive social security.

The original inhabitants of modern Uruguay and the arrival of the first Europeans

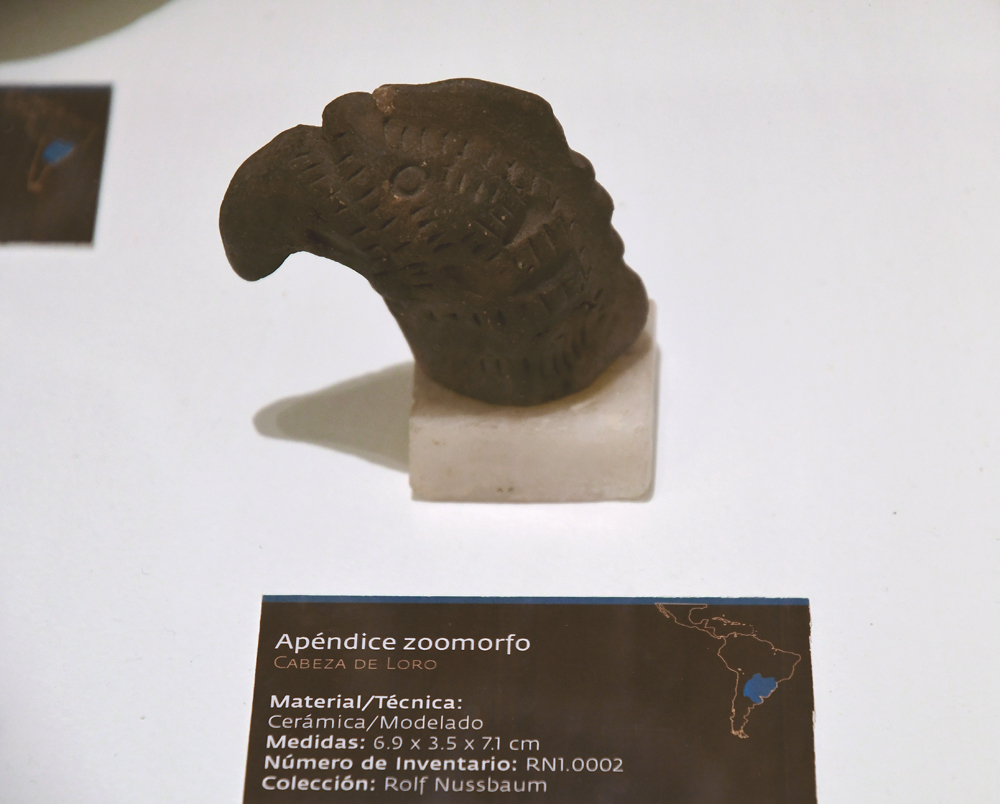

The territory of modern Uruguay was practically uninhabited, unlike many other regions of Latin America. Although, the earliest evidence of human settlements dates from the 11th century BC2.Chalupa, J.: Dějiny Argentiny, Uruguaye, Chile. NLN, Praha, 2002, p. 17., as remains of prehistoric stones in the northern part of the country3.See http://countrystudies.us/uruguay/2.htm#PRE-COLUMBIAN (Available at URL: 25. 9. 2016) , revealing little information about the people who created them.

The groups of people known as the Charrúa and Tupí-Guaraní did not come to this area until a few thousand years later. The reconstruction of their life and local traditions is almost impossible and everything that we know has been gathered from fragmentary manuscripts from European conquerors and settlers of the north of the vast estuary Río de la Plata, who were in contact with natives since early 16th century. The end of the 15th century and the first half of the 16th century became a period of discovery for Western Europe following the conquest and colonization of the New World and also a period of rivalry for naval powers, which would soon take a more prominent position.

Undoubtedly the most important events happened when Christopher Columbus crossed the Mar Tenebroso4.The Atlantic Ocean. and thus fulfilled his promise to the Spanish King – reaching Asia from the west.5.According to contemporary documents, Columbus lived in the belief that he had reached the shores of Asia until the end of his life. To be more specifically, the coast of Japan (Cipango) and he did not anticipate that he had reached the Caribbean. Moreover, he assumed that the rest of the country was India. More: Dějiny Španělska, NLN, Praha, 2007, pp. 225-228. Just two years later, the Vatican had to decide a dispute between the Portuguese and Spanish crowns about their entitlement to particular ´Asian´ territories. The dispute was finally resolved by the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) and it divided India into two hemispheres.

The eastern part was acquired by the Portuguese and the western part by the Spaniards.6.This division led to the fact that extensive areas of today´s Brazil fell to the Portuguese, on the other hand for the Spaniards, they were left in a disadvantaged position. See: Chalupa, 2002, p. 24. However, Columbus´ enthusiasm for the newly discovered territories of India was not echoed by his contemporaries and in 1507 Columbus´ view was finally refuted by the German cosmographer Martin Waldseemüller (1470-1520), who personally advocated that the newly discovered continent should be named after the Italian, Amerigo Vespuci, author of the ground-breaking leaflet Novus Mundus issued in 1503, as ´land of Amerigo´.

Amerigo Vespuci died in 1512 in the function of piloto mayor del reino7.The main royal navigator. and his successor was Juan Díaz de Solís. The Spanish King Ferdinand II. Aragon gave the task to Solís to explore ´the island of Ceylon, the Moluccas, Sumatra and Chinese country.´ (Ferdinand II. postulated that this area was actually located outside the Western Spanish demarcation line).8.Chalupa, 2002, p. 25. Nevertheless, the Portuguese fleet led by Vasco Balboa penetrated into the open Mar del Sur and the expectations of the Spanish monarch were broken – the vast expanse of the next ocean was uncovered. Therefore, he concluded a secret deal with Solís for an exploratory mission in 1514, which aimed to discover the connection between the two oceans.

The Royal navigator sailed along the eastern shores of South America until he reached the vast estuary of today´s Río de la Plata. He became convinced that he had discovered the connection between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and that he was at the current Venezuelan coast. So, he began to sail up the mouth of the river Uruguay to see the Mar del Sur. However, he encountered the native Charrúa, renowned for their fighting prowess, who captured most of the crew along with Solís, and then the remaining survivors were eaten before their own eyes. However, the unresolved issue remains of when Solís reached the Argentinian and Uruguayan shores9.There are various data. In this paper is described the year of 1516, but many authors and historians proposes the year 1508 or 1512, which would, of course, the above mentioned event shifted back. In any case, it is still remain the most preferred date 1516. and when and how he fell into the hands of the Charrúa. The above described event was handed down long after the death of Solís spread across Spain and many pages have been written to describe it. For example, the Italian Peter Martyr (1457-1526), a colonial chronicler, described the incident thus:

´He found the ominous and anthropophagic Caribs, about whom I have already talked extensively in other parts of this book. These Indians, in the manner of sly [female] foxes, feigned peace signs but were, in actuality, planning a sumptuous banquet. When they saw their guests from afar, they drooled like customers at a cheap dinner. Poor Solís landed with as many companions as the flagship boat allowed. A multitude of Indians left their hiding lair and attacked [the Spaniards] with sticks and killed them all before their companions´ [who have stayed on board the flagship] eyes. Later, the Indians destroyed the boat. Nobody escaped. Once, the Spaniards were all dead, the Indians cut them into pieces and prepared for the future banquet at the beach, while the rest of the crew watched the horrendous spectacle. Terrified by the atrocious episode, the others [on the flagship] did not dare to land or to avenge the death of their captain and companions and left those cruel beaches.´10.Mártir de Anglería 1892: Década III, Liber X, Caput II, 459-60 In: Verdesio, G.: Forgotten Conquests. Rereading New World History from the Margins. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2001, p. 16.

In this colourful description, where the Charrúas are depicted as Caribs, what is clear is that there were inaccuracies at the Royal courts on the actual shape and geographic area of North and South America and about where their crews landed. Moreover, it is worth noting the nickname man-eating, also the cunning (female) Fox and instead of dwelling, the use of the word dens. Such interpretations and reports about the indigenous people empowered the ideas of Europeans about their animal features and their diabolical cunning and therefore utter inhumanity – which subsequently led to the legalisation of the displacement of all the other natives of Latin America by the civilized Spaniards, then the Brazilians and Portuguese. There was also a connected story about a certain white ruler who resembled the ruler of El Dorado11.El Dorado or Gold-plated was a hidden mythological ancient city located in South America. It was made whole from pure gold, the city of prosperity and paradise, the Promised Land, which was ruled by a King, who instead of wearing clothes wore a layer of golden dust, which he washed away every night. This legend aroused the desire among Europeans between the 16th and 18th century for the discovery of such a splendour., whose name was Argentino12.Argentino or Silver. This was a similar fable to that mentioned above. This rumour become so widespread that it became the name of today´s territory of Argentina, and the river, which was discovered by Juan Díaz de Solís, was called the Río de la Plata (Silver River)., along with these rumours of ´animal beings´. These fables stimulated the interest of dedicated and hard-core individuals to find such rich pockets of gold and silver. According to the words of historian Julio César Chaves it was ´illusión de los grandes riquezas.´ 13.Ferguson, J.H.: The River Plate Republice. Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay. Time-Life Books, New York, 1968, p. 46

On the other hand, the murder of Solís discouraged the systematic colonization of the Uruguayan territory by the Spaniards in comparison to the neighbouring countries for a very long time. The entire area of today Uruguay was inhabited by about 5,000 indigenous people at the time of the arrival of the first Spaniards. The people speaking the Charruan languages were the most represented group. It is a language cluster associated with Chanás, Yaros, Bohanes and others. Charrúa were typical hunter-gather groups of nomads wandering across the Argentine and Uruguayan pampas, building up simple dwellings. Their society was stratified and peculiarly for them, their numerical system was based around the number 4. From a broader historical perspective of Uruguay, the beginning of the 17th century was essential, since the Paraguayan Governor Hernando Arias de Saavedra (1561-1634) decided to explore the secluded parts of the Charrúa region.

The view on the Uruguayan pampa with its endless grassy plane bordered by the Atlantic ocean on one side and surrounded by the river Uruguay on the other side, led him to the conclusion that there was no more suitable region for livestock. He regularly confided such dedicated thoughts through letters to the Spanish King, but there was no answer. Therefore, Hernandarias proceeded to this decisive step, and between 1611 and 1617 he brought onto the grassy plains his own cattle and horses from Estancia Santa Fe. The initiative showed huge success because the herds could move freely and so multiplied rapidly. The increasing numbers of herds lured faeneros from the surrounding areas to slaughter the cattle, which led to the general prohibition of establishing human settlements in Uruguayan lands. Finally, the area changed into reservation land for a long time and remained uninhabited again. Uruguayan historians succinctly wrote about this period that cows and horses came ahead of human colonization of the country.

Husbandry became the main source of Uruguayan prosperity until the 20th century. Also the Charrúas had to adapt to changing circumstances and therefore became capable riders and prospered from wild animals, eventually trading with the Spaniards. It should be noted that the Charrúa rejoiced briefly in the new face of the pampa and what became the basis of the lifestyle and economy of the Uruguayans, which meant the ultimate end to the itinerant Charrúa. Additionally, one of the biggest, and also ultimately shocking events happened on 11th April, 1831, known as the massacre in Salsipeude in Puntas del Queguay. On this day the main Charrúa chiefs were called ´to discuss the protection of state borders´ next to the Bernado Rivera. It was an ambush and, in the end, most of the Charrúas were captured and sent into exile or slaughtered.

The organized massacre was the ultimate end for Charrúa people. Those who survived were introduced into Europe as ´exhibition specimens´, where they contacted diseases and died shortly after arriving. Today, there is a pieta called ´Los últimos Charrúas´ in Montevideo to commemorate the last four of the Charrúas, who were captured near Salsipuedes. There was a shaman, Senaca, a warrior, Vaimaca-Piru and a couple; Tacuabé and Guyunusa.

These four Charrúa were taken to Paris and exposed as exemplars to the public. In response to the change of environment and traumatic experiences, they died soon. The remembrance of the Charrúas is still alive in the minds of Uruguayan people. For example, the Urugayan sports teams choose the names connected to Charrúas to proudly highlighted their courageousness and combativeness. Currently, there are no indigenous Charrúa in Uruguay. On the other hand, there is a number of mestizos living in Argentina, Brazil and also in Uruguay, totalling between 160 000 and 300 000. This culture and language is experiencing a kind of revival these days and so there is an endeavour to revitalize the culture and language.

José Gervasio Artigas and the battle for independence

Since the days of establishing the first missionaries14.The oldest Spanish settlement, called Santo Domingo de Soriano, was founded in 1625 by two Franciscans. and settlements, there has been a designation of ´Banda Oriental´15.Literally the Eastern Shore. for the territory of Uruguay to distinguish from the ´Banda Occidental´16.Literally the Western Shore., the two parts of the country divided by the river of Uruguay. Thus, the residents of the Banda Oriental have become known as Orientales and the future national identities of modern Uruguayans were formed at this time. The characteristic features of the Orientales were being unrestrained and having a tendency for a kind of nomadism (somewhat similar to Charrúas´ way of life). Nevertheless, the land was a country of roamers, gauchos, faeneros and grass roots people, who had to struggled for their survival and also faced the Charrúa´s raids. The region resembled, with its atmosphere and morals, the Wild West, until the late 18th century. For example, contemporary manuscripts describe the period as follows:

´The murders in the Uruguayan countryside are the most terrifying that you can see in the whole New World. Men are ripped like pigs with long knives and often the only reason is the desire to kill. We saw two condemned men who stated that the reason for their acts was the desire to end their miserable lives on the gallows. Almost nobody feels the fear of justice here and the God is unknown.´17.´Vraždy na uruguayském venkově patří k tomu nejděsivějšímu, co lze v Novém světě spatřit. Muži jsou dlouhými noži rozpáráni jako prasata a často je jediným důvodem touha zabíjet. Viděli jsme odsouzence, kteří jako důvod svého činu uvedli touhu skončit svůj bídný život na šibenici. Strach ze spravedlnosti tu necítí skoro nikdo a Boha zde neznají.´ Chalupa, 2002, p. 82.

These prevailing hard conditions in the Uruguayan rural areas did not stop the growing self-awareness of the Orientales and their dissatisfaction with the colonial powers. One of the presumptions of this fact was pressure from the Portuguese, who were increasingly pushed to the south and eventually crossed the demarcation line from 1494. In 1680, the Portuguese founded the settlement of Colonia del Sacramento in Uruguayan territory, whose existence or non-existence was disputed by the Spanish and Portuguese authorities. Finally, everything was decided in favour of the Spaniards. First of all, there was the established fortress of San José in the beginning of the 18th century, by the governor Bruno Mauricio de Zabala. Secondly, the Spanish control was definitely fixed by establishing the strategically important port of Montevideo in 1724. Montevideo became the centre of the country very shortly after.

In 1777, Colonia do Sacramento was destroyed by the Spaniards and the Portuguese were expelled. The Portuguese, despite this, did not stop dreaming about occupying the Uruguayan territory and seizing the strategical points on the river in the La Plata area. Furthermore, the Orientales did not feel pressure only from northern Brazil. The port of Buenos Aires in the south increasingly pushed ahead in the role of a centralist hegemon and monopolist in the sphere of local trade. This hostility between Orientales and Porteños18.Literally ´people from the port´. grew in size. The final straw in the quest for freedom was on 3rd February, 1807, when the English occupied Montevideo and so the Orientales had to make great efforts to repel the ´intruders´ in the same year. These events just strengthened the autonomist-minded Uruguayan people and the desire for freedom became everything.

One such person longing for freedom was the son of the first inhabitants of Montevideo, José Gervasio Artigas (1764-1850), who recognized the necessity of enforcing Uruguayan independence and the removal of the shackles of the dominant Porteños. Artigas´ idea consisted of the formation of an independent province (from Spain) and then joining with the independent United provinces of La Plata. José Gervasio Artigas started his revolutionary career by joining the May revolution19.The May revolution (La revolución de Mayo) took place in 1810 in present day Argentina and reflected the events, which had happened in Spain, which had been occupied by the French. The news swiftly spread through the Spanish colonies. The changing events in Europe had been used to the realization of rebellions and revolutions against the Spanish domination. To sum up, the May Revolution became a model for Artigas´ revolution, which eventually led to Uruguayan independence. in 1811. While Artigas was staying outside Montevideo, an armistice between the two main ports of Montevideo and Buenos Aires was agreed, which was absolutely unthinkable for the followers of Artigas. These people called loudly for freedom, adored Artigas and for this reason they took after him.

According to historical sources, in January, 1812, the number of people who supported Artigas and went to him reached a staggering 16, 000, which was an incredibly high number of people, if we take into account that the total population did not exceed 50,000 in the entire East Coast. Therefore, the whole scene of wandering men, women and children and old people echoed a biblical scene of exodus.20.Ibid, pp. 99, 101. The first great victory was achieved by the freedom fighters on 18th May, 1811, near the river of ´Las Piedras´. At the beginning, the freedom fighters were supported by an independent military junta from Buenos Aires. However, a split occurred when Artigas demanded complete independence from Spain, and moreover the equality of all people (!). The reply not take a long time and Artigas received an answer quickly in the form of war between him and the junta from Buenos Aires.21.Chalupa, 2002, pp. 103-104. Finally, Artigas was deported to Paraguay and the Portuguese occupied the East coast.

The deportation of Artigas to Paraguay inspired the famous ´33 Orientales´ (patriots par excellence), who started a huge campaign for the freedom of Uruguay, under the leadership of Juan Lavalleja, and the end of the occupation by Brazil. In 1828, an agreement was negotiated between Argentina and Brazil from a British initiative, where all parties respected the new state.22.Bernhardson, 1996, p. 603.

From a national point of view, the events described above are still very important for modern Uruguayan people and Artigas has literally become a legend. For example, every year Artigas´ Day (Natalicio de Artigas) is celebrated, which falls on the 19th of June, the day when Artigas was born. As well as a public holiday, banks, offices and some markets are closed. The people gather in the centre of Montevideo, ´Plaza Independencia´, and participate in the festivities.23.Uruguay. Society and Culture. World Trade Press, Petaluma, 2010, p. 5. A feast is also held for the remembrance of the victorious battle at Las Piedras (Battalla de las Piedras) on May 18 and also for the 33 Orientales (Desembarco de los 33 Orientales), whose feast day is April 19.

The song ´A Jose Artigas´ by the Uruguayan singer, songwriter, poet and journalist, Alfredo Zitarrosa (10. 3. 1936 – 17. 1. 1989), who specialized in the Uruguayan and Argentine folklore genres.

Uruguay after independence in the 19th century

The obtaining of independence did not bring the desired stability and there were approximately 40 uprisings and anti-government riots between 1830 and 1904.24.Chalupa, 2002, p. 271. The country had been gripped by political chaos, civil wars and it went through the most changes of all the countries in Latin America. In 1880, the military dictator Latorre resigned with the words that these are people ´ incapable of being governed´.25.Pendle, G.: A History of Latin America. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1973, p. 189. During the 19th century, Uruguay underwent extensive demographic changes. In 1830, the population had been around 80, 000 inhabitants and by the early 20th century the number was closer to one million. This was caused by a huge wave of European immigrants26.It was around 400, 000 people in the 19th century., who mainly inhabited Montevideo. This immigration has become a determining phenomenon for Uruguay and the country was truly the ´homeland of foreigners´.27.Chalupa, 2002, pp. 271-273.

Furthermore, it was also a country of merchants and ranchers. The Uruguayan tasajo (beef), which was dried in saladero28.Saladero is a place, where cattle were slaughtered and then the meat was salted and dried., became a popular commercial commodity. The tasajo was exported especially to Brazil or Cuba, where it was used as food for slaves on plantations. If we compare campiña29.Countryside, rural area. to Montevideo, they were two different worlds. The Uruguayan countryside was the homeland of the gauchos, ´free men on horseback, fed by the wind´30.Chalupa, 2002, s. 508.. However, the way of life of the gauchos was pushed aside and replaced by the settled estancieros31.The landowner; the owner of estancia.. The port of Montevideo became a place where merchants and cattlemen from rural areas came to sell leather and meat and also see the latest European fashion trends and achievements.

Gradually, pride for ´Uruguayan Europeanism´ had been growing across the social groups and this was one of the main differences, which distinguished Uruguay from other Latin American countries. Nevertheless, people in Montevideo have still not forgotten their colonial past and some kind of animosity between Buenos Aires and Montevideo still exists. At the same time with the increasing prestige of the Uruguayan port, amusing stories about the Porteños began to emerge, and they were singled out from the rest of the Argentinians. The process of formation of national pride and patriotism was also determined by the geographic context. Uruguay is a small state, literally wedged between the two enormous worlds of Argentina and Brazil. Uruguay had to compete with these countries during the difficult times and maintain its independence. For example, one of the most important figures was José Pedro Valera (1845-1879), who started the modern process of transforming the whole of Uruguay. José Pedro Valera had studied in the United States since 1867, and then returned to promote the necessary changes. He was aware that the social situation in Uruguay was not so urgent compared to the other countries of Latin America. On the other hand, only one child in fifty attended elementary school and so the nation was still mostly illiterate. For this reason, Valera pushed for educational reforms to take place, which led to a free and compulsory schooling system.32.Pendle, 1973, pp. 189-190. Finally, Valera´s reforms were one of the major changes in the 20th century in Uruguay and for this reason, he has become one of the most important historical figures for the Uruguayan nation.

The transformation of Uruguayan society in the 20th century

It could be said that the transformation of Uruguayan society occurred in the 20th century thanks to José Batlle y Ordóñez (1856-1926), one of the most prominent figures in Uruguayan history. José Batlle y Ordóñez had been engaged in the issues of political life in Uruguay since his studies at the University of Law. Later, a resentful Ordóñez left the university due to the prevailing atmosphere and the fact that university was formed of only the ´powerful loyal political elite, ready to take over the sceptre from the previous establishment.´33.Chalupa, 2002, p. 305.

José Batlle y Ordóñez was elected as president, firstly in 1903 and until the end of his life he enforced a large number of legislative changes. For example, he introduced the eight-hour workday, instituted regular pensions for retirees and other crucial social measures. Moreover, he introduced a law, which allowed divorce on the terms of women and ratified a ban on capital punishment and also bullfighting. José Batlle y Ordóñez also advocated for state-owned public services.34.Pendle, 1973, p. 191. It follows that José Batlle y Ordóñez enjoyed immense popularity, especially for his ability to ´reconcile the interests of the modern thinking bourgeoisie with the rising demands of the popular social classes to improve their working and living conditions.´35.Chalupa, 2002, p. 305 On the other hand, his transformation process and reinforcement of a number of new laws was not met with only enthusiasm. There was also a strong opposition, composed of many conservative-minded opponents who called him a fool. Even a diplomat from Franco´s Spain expressed his utter disgust over the fact that Uruguayans did not undertake mandatory military service, claiming that they do not have respect for military officers and moreover there is a lack of ´macho´ bullfighting (!) during his visit to Uruguay.36.Pendle, 1973, p. 191.

Uruguay had undergone a number of secular transformations, teaching at schools no longer took place according to a classic Catholic teaching system. However, it was not only the president who changed the face of Uruguayan society. The country also established a program of economic modernization and increasingly focused on the frozen food industry, which replaced the famous tasajo. Uruguayan wool, not only Uruguayan beef, was a popular market commodity. The trade in wool also led to a rise in the middle classes in the Uruguayan population, since sheep farming was less expensive and could be done by almost everyone. These changes were also accompanied by increasingly large waves of immigrants seeking new work opportunities. There were also a large number of patriotic publications and an increasing Uruguayan national awareness after the death of President José Batlle y Ordóñez. For example, in Libro del Centenarion del Uruguay, from 1925, we can read:

´Our success in all sorts of areas of human activity that have been achieved since the days of independence until now, should be stressed both at home and abroad. (…) the promised land, beautiful, living in perfect harmony, with perfect laws. The country open to all races, nations and ideas.´37.Chalupa, 2002, s. 321.

The above mentioned achievements in Uruguay were truly experienced in the form of unprecedented flourishing of trade exports, although it was eventually replaced by stagnation. There were a number of popular strikes and discontent in Uruguayan society, caused by the worldwide fall in demand for agricultural products over the 1950s. The urban guerrilla group, Tupamaros, which appeared during the 60s in the form of violent insurrection and led up to the military coup in 1973. The military junta ruled the country until 1985, when democratic reforms were re-established.

Currently, Uruguay is one of the richest countries in Latin America, as well as Chile (measured by GDP per capita). Uruguay still has a thriving economy, although is currently suffering from 20% unemployment. Despite the secular nature of Uruguay, there are Christmas and Easter holidays. These annual holidays are accompanied by the above-mentioned national festivities, important for Uruguayan history.

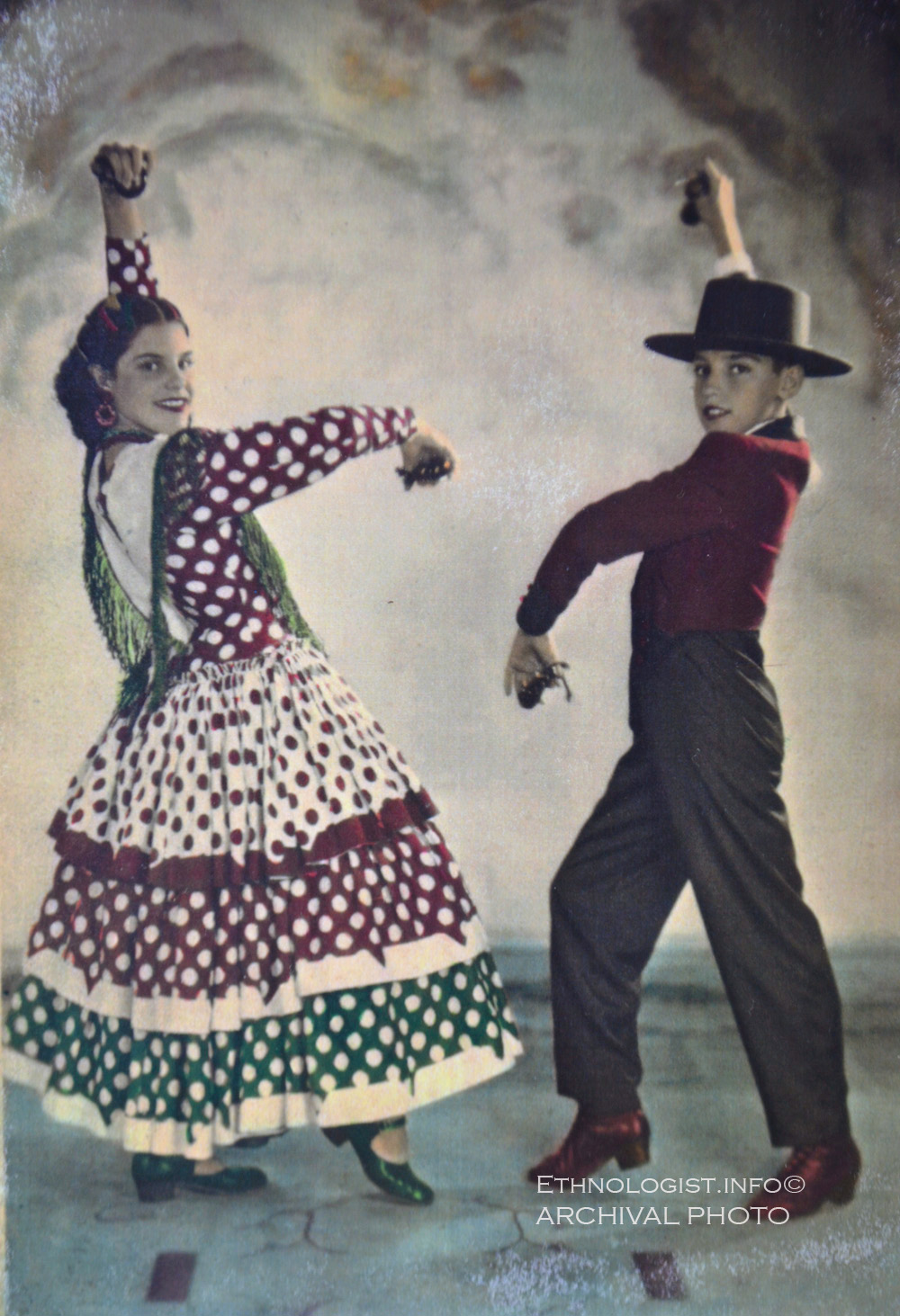

There is also a classic annual carnival procession, or feast, as in Brazil, bonding the African-Christian festivals, called Virgen de la Candelaria. During this celebration, which is held on February 2nd, people gather on the beach in Montevideo and in Punta del Este. People dress in blue and white dresses and put into small boats a number of gifts (such as flowers or candles) for the goddess of the sea, Imanje (also known as St. Anna). This feast came to Uruguay with the African slaves, who were transported to the neighbouring countries, such as Brazil.

Conclusion

Finally, Uruguay can be characterized as one of the most European countries of Latin America, which, on the other hand, honours the memory and traditions and cultures of both the indigenous people and the European immigrants. People in Uruguay are aware of their deeper European roots, while the Uruguayan country has changed them and also distinguished them (eg. the way of life of the gauchos or landowners). The country also had a nickname ´The Switzerland of Latin America´, through the first half of the 20th century. Uruguay was characterized by low numbers of population and so remained a country of large meadows with grazing cattle. Despite its secular character, the country is formed mainly from Roman Catholics and the main religious holidays are Christian.

| ↑1 | República Oriental del Uruguay. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Chalupa, J.: Dějiny Argentiny, Uruguaye, Chile. NLN, Praha, 2002, p. 17. |

| ↑3 | See http://countrystudies.us/uruguay/2.htm#PRE-COLUMBIAN (Available at URL: 25. 9. 2016) |

| ↑4 | The Atlantic Ocean. |

| ↑5 | According to contemporary documents, Columbus lived in the belief that he had reached the shores of Asia until the end of his life. To be more specifically, the coast of Japan (Cipango) and he did not anticipate that he had reached the Caribbean. Moreover, he assumed that the rest of the country was India. More: Dějiny Španělska, NLN, Praha, 2007, pp. 225-228. |

| ↑6 | This division led to the fact that extensive areas of today´s Brazil fell to the Portuguese, on the other hand for the Spaniards, they were left in a disadvantaged position. See: Chalupa, 2002, p. 24. |

| ↑7 | The main royal navigator. |

| ↑8 | Chalupa, 2002, p. 25. |

| ↑9 | There are various data. In this paper is described the year of 1516, but many authors and historians proposes the year 1508 or 1512, which would, of course, the above mentioned event shifted back. In any case, it is still remain the most preferred date 1516. |

| ↑10 | Mártir de Anglería 1892: Década III, Liber X, Caput II, 459-60 In: Verdesio, G.: Forgotten Conquests. Rereading New World History from the Margins. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2001, p. 16. |

| ↑11 | El Dorado or Gold-plated was a hidden mythological ancient city located in South America. It was made whole from pure gold, the city of prosperity and paradise, the Promised Land, which was ruled by a King, who instead of wearing clothes wore a layer of golden dust, which he washed away every night. This legend aroused the desire among Europeans between the 16th and 18th century for the discovery of such a splendour. |

| ↑12 | Argentino or Silver. This was a similar fable to that mentioned above. This rumour become so widespread that it became the name of today´s territory of Argentina, and the river, which was discovered by Juan Díaz de Solís, was called the Río de la Plata (Silver River). |

| ↑13 | Ferguson, J.H.: The River Plate Republice. Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay. Time-Life Books, New York, 1968, p. 46 |

| ↑14 | The oldest Spanish settlement, called Santo Domingo de Soriano, was founded in 1625 by two Franciscans. |

| ↑15 | Literally the Eastern Shore. |

| ↑16 | Literally the Western Shore. |

| ↑17 | ´Vraždy na uruguayském venkově patří k tomu nejděsivějšímu, co lze v Novém světě spatřit. Muži jsou dlouhými noži rozpáráni jako prasata a často je jediným důvodem touha zabíjet. Viděli jsme odsouzence, kteří jako důvod svého činu uvedli touhu skončit svůj bídný život na šibenici. Strach ze spravedlnosti tu necítí skoro nikdo a Boha zde neznají.´ Chalupa, 2002, p. 82. |

| ↑18 | Literally ´people from the port´. |

| ↑19 | The May revolution (La revolución de Mayo) took place in 1810 in present day Argentina and reflected the events, which had happened in Spain, which had been occupied by the French. The news swiftly spread through the Spanish colonies. The changing events in Europe had been used to the realization of rebellions and revolutions against the Spanish domination. To sum up, the May Revolution became a model for Artigas´ revolution, which eventually led to Uruguayan independence. |

| ↑20 | Ibid, pp. 99, 101. |

| ↑21 | Chalupa, 2002, pp. 103-104. |

| ↑22 | Bernhardson, 1996, p. 603. |

| ↑23 | Uruguay. Society and Culture. World Trade Press, Petaluma, 2010, p. 5. |

| ↑24 | Chalupa, 2002, p. 271. |

| ↑25 | Pendle, G.: A History of Latin America. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1973, p. 189. |

| ↑26 | It was around 400, 000 people in the 19th century. |

| ↑27 | Chalupa, 2002, pp. 271-273. |

| ↑28 | Saladero is a place, where cattle were slaughtered and then the meat was salted and dried. |

| ↑29 | Countryside, rural area. |

| ↑30 | Chalupa, 2002, s. 508. |

| ↑31 | The landowner; the owner of estancia. |

| ↑32 | Pendle, 1973, pp. 189-190. |

| ↑33 | Chalupa, 2002, p. 305. |

| ↑34, ↑36 | Pendle, 1973, p. 191. |

| ↑35 | Chalupa, 2002, p. 305 |

| ↑37 | Chalupa, 2002, s. 321. |