Ethnogenesis describes the early nation-building process of Somalis, about whom references can be found in Ethiopian written records from at least the beginning of 1500 AD, under the name Somalis.1.The term ‘Somalis’ appears for the first time in a famous poem dedicated to the victory of the Ethiopian Negus Ješaqa (who ruled from 1414 to 1429) over the Muslim kingdom Ifat. See LEWIS, I. M.: The People of The Horn of Africa. International African Institute, London, 1955, p. 13. However, details from that time are still unclear and there is no comprehensive view of the ethnogenesis of the Somalis in existence. There are a number of scientific hypotheses, based on the results of social disciplines, which can be used to interpret the history of societies that did not have knowledge of writing. These include anthropology, archaeology and history. The significant factor, which led to complications in this research, is that the Somali language was not fixed and codified into writing over time.2.Until 1972, the Somali language was a non-written language. As a result, attention has focused mainly on research outputs from historical linguistics and its reconstruction of language (in this case the Cushitic languages), and this could clarify some historical connections among cultures in East Africa.

Ethnogenesis of the Somali people

The study of the etymology of the name ‘Somali’ brings similar problems and offers different explanations. The first explanation finds a connection between the words so (go) and mal (milk). This could reflect and refer to the traditional Somali nomadic way of life. Another explanation may be that the name is a derivation from salama (to be a Muslim),3.ABDULLAHI, M. D.: Culture and Customs of Somalia. Greenwood Press, Westport, London, 2001, p. 8. which would reflect the fact that Somali society is overwhelmingly Muslim. Alternatively still, it could be a derivative of Samaale or Somaal – the designation for a group of people who, according to German linguist B. Heine, occupied almost the entire territory of the Horn of Africa in around 100 AD.4.FITZEGERALD, N. J.: Somalia. Issues, History and Bibliography. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., New York, 2002, p. 32. Heine also proposed that the southern highlands of Ethiopia could be considered as the original homeland for the proto-sam, the immediate predecessors of the Somalis.5.ZAHORIK, J.: The Early History of the Somali and the Discussion on Baiso – an overview. In: Machalík, T., Zahorik, J. (eds.): Viva Africa 2007. Proceedings of the IInd International Conference on African Studies. Dryada, Pilsen, 2007, pp. 95-106.

There is another view that places the motherland of the Somalis on the west coast of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden.6.Somali narrative history perceives this area as the original homeland of the biggest Somali clans. See ABDULLAHI, 2001, p. 8. This assumption was held by earlier historians and put the theory into the context of Arab immigration to the Somali coast, thus creating the ethnogenesis of the Somali people.7.Earlier historiographies have taken the view that Somali people originated by mixing of the population of black Africa with the population of the Arabian Peninsula. Today, this theory is not an adequate scientific or academic explanation for the origin of Somalis and their history. However, it is not disputed that coastal cities existed and there was a continuity of relations between the two regions, but these links are not sufficient to form an entire ethnic group and the Arab migration to the Somali coast does not seem as strong as previously assumed. This theory has been largely disproven, but it is important for this paper. This idea was the key factor that shapes the self-identification process of the main Somali clans. At the head of Somali clans stands an important Arab ancestor (in the most cases, a sheikh),8.Originally, this terms was the title for the Arab tribal leader (chief); later it was applied to the leaders of Sufi brotherhoods. who is adopted and integrated into Somali society. This practice placed the Somali clans into a broader cultural cluster and also into a ‘sacred history’. However, there is a certain ‘superstructure’ in the way that Somalis identify themselves: the Somali people, as a nation, still recognise their mythical ancestor Samaale, from whom they derive their origin. It must be noted that in this concept, the mythical ancestor is compatible only with Somalis, not the ethnic group of Sab,9.LEWIS, 1955, p. 14. who, in the modern conception of nationality, are Somalis.10.In this paper the term ‘Somali clans’ includes Somalis and Sabs.

Despite all the aforementioned theories, thanks to rigorous comparative studies of the early Somalis, it seems the most likely hypothesis for the ethnogenesis of Somalis in the region is that they came from modern southern Ethiopia and north-eastern Kenya. On the other hand, theories based on the Somali narrative history cannot be ignored, placing the origin of certain Somali clans in the northern parts of Somalia (e.g. the clan of Isaaq or Daarood). The formation of the Somali people may have taken place after extensive migrations within the Horn of Africa. The Somalis should therefore be considered as direct descendants of the ancient Cushitic nations, whose descendants are still connected with a number of significant symbols and features, especially the language and the remains of the Cushitic religion. Nonetheless, the Somalis do not identify or share general solidarity with the other Cushitic ethnic groups (for example with Oromo or Afar people). Instead, they emphasise their ethnic origin as being from Arab immigrants, during an important historical period that began in the 7th century AD, the beginning of the Muslim era. This began not only continuous links with the Arab world, but above all was the initial impetus for the later formation of Somali clans.

At the same time, all Somali clans are not assumed equal simply for the reason that they profess Islam or have been endowed with the noble lineage of Arab ancestry. There is some antagonism between tribes and clans, those that are more or less noble, which have been mixed with surrounding populations and ethnicities. On the whole, Somali society has become extremely varied: allegiance to a particular clan or tribe defines a person’s social status, rights and duties and, in most cases, predicts their lifestyle.

In conclusion, there are two levels of understanding of the ethnogenesis of Somalis: the ‘real’ understanding, based on linguistic affiliations and physical anthropology, and an ‘imaginary’ understanding, based on the religious aspects of Somali society or mythical events. The ‘imaginary’ structure of society determines their life.

The Somali language

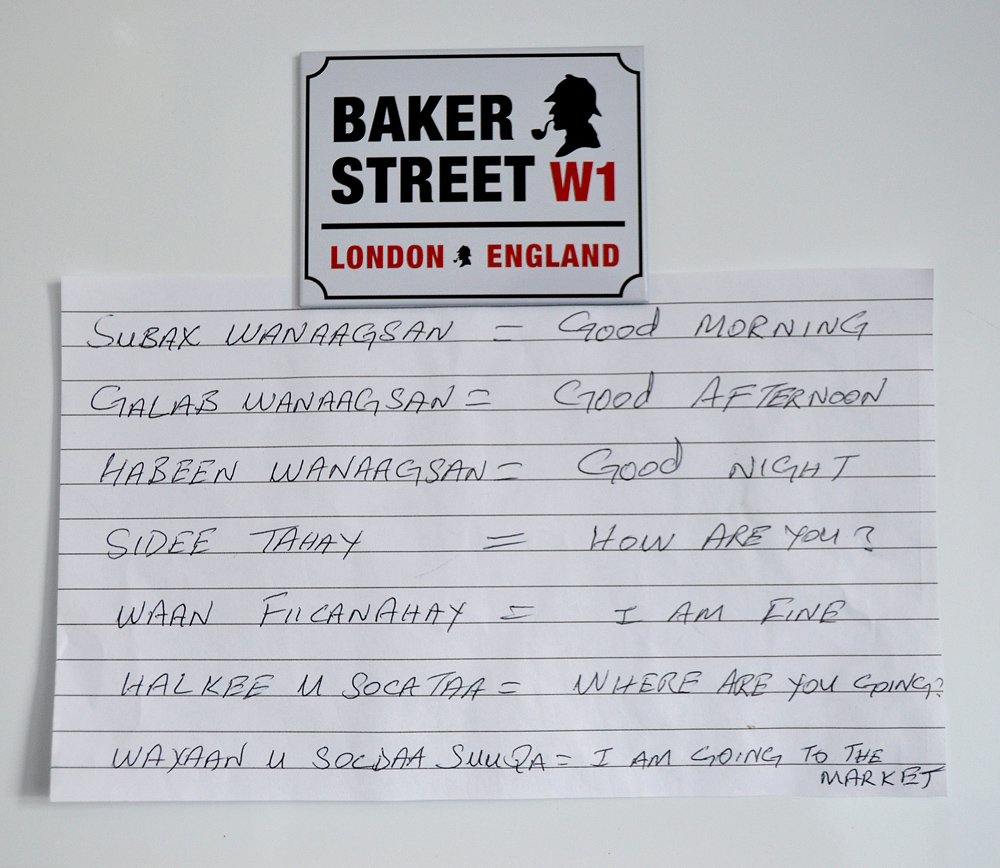

The Somali language, as indicated above, was not codified until the second half of the 20th century,11.An exception to this is the manuscript of the phonetic transcription of the Somali language, which had already been created by the ruler of the sultanate Majeerteen Cusmaan Yuusuf Keenadiid around 1920. This transcription is known as ‘Cusmaanya’ and was considered as one of the options for the modern standard form of the Somali language during the 1960s and ’70s. LEWIS, I. M.: Saints and Somalis. Popular Islam in a Clan-based Society. The Red Sea Press, Inc., Asmara, 1998, pp. 49-50. although its older forms have been spoken since prehistoric times. Generally, modern linguists are consistent in their view that Somali is a branch of the Afro-Asiatic (semito-hamits) language family. This language family is divided into the clusters of Hausa languages, Cushitic languages and Semitic languages. Amharic, Arabic and Hebrew belong to the Semitic languages, while Somali, Afar and Oromo are among the Cushitic languages. The Somali dialects are recognised as so-called General Somali, Coastal Somali and Central Somali.12.FITZEGERALD, 2002, p. 48.

General Somali became the basis for the later codification of the national language, which was approved by the Somali language committee, legalised and declared on 21 October 1972 by the government of the Somali Democratic Republic.13.Somali democratic republic (1969-1991), President Maxamed Siyaad Barre. Since the overthrow of Barre, the official name of the country has been the Somali Republic. From religious and political points of view, the biggest debate was over the form of transcription the Somali languages would take. Society has been divided. Some supported converting Somali into the Arabic alphabet, for example arguing that: ‘the spiritual lives of ordinary Somalis would be strengthened if the language were to be transcribed in the script of the holy Qur´an.’14.JOHNSON, J. W.: Orality, literacy, and Somali oral poetry. In: Journal of African Cultural Studies, Vol. 18, N. 1, 2006, p. 122. On the other, there were also those who thought that: ‘the consonantal writing system of Arabic with only three diacritics for vowels (…) was inadequate for vowel-rich Somali.’15.Ibid.

Eventually, the transcription created by linguist Shire Jaamac Axmed in Latin characters was accepted. The famous academicians B. W. Andrzejewski and Muse H. I. Galal also significantly influenced the Somali codification. These three names are seen as the synonymous for the founding fathers of the modern Somali language.16.See ABDULLAHI, 2001, p. 73. During the two years following codification, there was a nationwide campaign for supporting and promoting literacy among the general Somali population. This process was considered a form of ‘domestic colonialism’, especially by the speakers of the Af Maay dialect (spoken by clans of Sabs) and by speakers of Benadir coast. These dialects are significantly different from General Somali17.General Somali, sometimes called Northern Somali or North-Central Somali. For more information see JOHNSON, 2006. It has appeared in numerous publications and newspapers, for example periodically in the Xiddigta Oktoobar (October Star), to describe events as well as being used by authors publishing serial story-telling, which is very popular with Somalis.18.Njogu, K.; Moupeu, H. (ed.): Songs and Politics in Eastern Africa. Mkuki na Nyota Publishers Ltd., Dar es Salaam, 2007, p. 362. The Somali language has been transcribed successfully and this has kick-started the activities of Somali national revivalists and national writers.

However, despite these turbulent and ground-breaking years, which were often accompanied by controversy, the Somali language has continued to be spread in oral form, as it has always been. The most important factor in this spread has been the historical context of Somalia. The country has never been incorporated into expanding and powerful caliphate empires and kingdoms, which would pursue efforts for strongly centralised systems of management to enforce mandatory taxes in kind or money, as was the case for the Middle East or in the old continent. The process of centralisation of expanding state units required specific, appropriate systems of officials and scribes for detailed accounting of the economics of the state. The Somali territory avoided being pulled into such a system almost until the arrival of colonial powers and thus there was not a climate for developing a ‘textual society’, although there were some coastal areas where small principalities and sultanates rose and fell, depending on the transit trade and relations with the Arab Peninsula.19.In this case I meant only strictly the Somali coastal areas, not for example coast of Swahili civilization, which has developed a writing system based on a synthesis of Arabic and Bantu language and could form a unique civilization stretching from the Somali Mogadishu to Mozambique Sofala (included forty cities) at the end of 13th century. The Swahili language had been written in Arabic script until 18th century and then it took the Latin alphabet. However, the rulers of the small sultanates were satisfied with using the Arabic language, which was a kind of lingua franca20.Lewis compares Arabic spoken across the Somali region with the Latin of medieval Europe. See LEWIS, 1955, p. 11. in those days and they often welcomed scholars and saints from the sacred land of Arabia, who inscreased their knowledge. This process has preserved mainly Arabic religious tracts and poems as classical Arabic qasída21.Poetic form traditionally does not exceed 100 verses. It has the character of the poetic form of pre-Islamic Arabia and even today enjoys huge popularity. or manáqib22.Memorable acts, hagiographic literature. dedicated to Sufi saints and Sheikhs.

The second factor in the spread of the Somali language follows from the points mentioned above. The sultanates were often concentrated along the Eritrean and Somalian coasts and were connected with central areas of Africa though the caravan routes and their trading stations. So, Arabic language did not affect the surrounding traditional rural areas, where a pastoral and semi-nomadic way of life dominated. The Somalis who lived inside and outside these sultanates developed their own unique culture based on absolute orality that also reflects the organisation of rural Somali communities.

Each kinship and clan was based on the traditional patriarchal pattern and has retained a group of elders even today, who are guardians of a collective tradition and knowledge. The elders, like every Somali warrior or waranle,23.Warrior (literary spear-messenger). The term is applied to all adult men but does not include men who dedicate their life to God (see term wadaad). Women are also excluded from this classification and cannot become warriors. should have a skill in persuasive speaking according to his personal qualities. The Somalis may be described as natural born ‘orators, poets and narrators.’24.LEWIS, I. M.: Understanding Somalia and Somaliland. Culture, History, Society. Columbia University Press, New York, 2008, p. 23. The waranle must be able to succeed in disputes and polemics and the elders deserve to be recognised for the memorability of their mostly improvised narrative story-telling. As a result, Somali traditional society has not generally required literacy skills; in situations where they were necessary, people turned to the wadaad,25.Wadaad (pl. wadaddo) refers to men who are connected with religion, such as spiritual or ritual leaders, religious officials or members of Sufi’s orders. The term excludes warriors. Hierarchically, wadaad stands below the sheik (meaning sacred term), who express the highest spiritual and divine power and respect. the wise man who had knowledge of Holy scripture (Arabic), Qur’an and hadiths.26.Records of the statements and deeds of the Prophet Muhammad. After the Qur´an, the second most important source of Islamic religious law.

Modernity has blurred these deep-seated differences between rural and urban society. Those who excel in linguistic and rhetoric art could be written and so, his poetry and story could have a written form or it could be recited by hafadiyaal.27.Memorisers: see ABDULLAHI, 2008, p. 71. The poetry could also be recorded on any audio voice recorder which would highlight the author’s powerful voices and create a deeper artistic listening experience.

The Somali language has become an important factor in shaping national and cultural awareness over the last few decades since its codification. The development of written Somali has enabled many Somali authors not only to make themselves well-known but also has shaped the Somali intellectual sphere. The Somali people, as well as their language, have a unique national identity that has been emancipated. This makes Somalia so much more than an island in the huge sea of the Arab world.

Bibliography

ABDULLAHI, M. D.: Culture and Customs of Somalia. Greenwood Press, Westport, London, 2001.

FITZEGERALD, N. J.: Somalia. Issues, History and Bibliography. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., New York, 2002.

JOHNSON, J. W.: Orality, literacy, and Somali oral poetry. In: Journal of African Cultural Studies, Vol. 18, N. 1, 2006.

KROPÁČEK, L.: Súfismus. Dějiny islámské mystiky. Vyšehrad, Prague, 2008.

KUBÁT, P.: Su´lúkové – tuláci arabských pustin. Zbojnická poezie v předislámské Arábii. In: Nový Orient, Vol. 65, N. 2, 2010.

LEWIS, I. M.: Saints and Somalis. Popular Islam in a Clan-based Society. The Red Sea Press, Inc., Asmara, 1998.

LEWIS, I. M.: The People of The Horn of Africa. International African Institute, London, 1955.

LEWIS, I. M.: Understanding Somalia and Somaliland. Culture, History, Society. Columbia University Press, New York, 2008.

NJOGU, K.; MOUPEU, H. (ed.): Songs and Politics in Eastern Africa. Mkuki na Nyota Publishers Ltd., Dar es Salaam, 2007.

OLIVERIUS, J.: Svět klasické arabské literatury. Atlantis, Brno, 1995.

REID, R. J.: Dějiny moderní Afriky od roku 1800 po současnost. Grada Publishing, Prague, 2011.

ZÁHOŘÍK, J.: The Early History of the Somali and the Discussion on Baiso – an overview. In: Machalík, T., Záhořík, J. (eds.): Viva Africa 2007. Proceedings of the IInd International Conference on African Studies. Dryada, Pilsen, 2007.

| ↑1 | The term ‘Somalis’ appears for the first time in a famous poem dedicated to the victory of the Ethiopian Negus Ješaqa (who ruled from 1414 to 1429) over the Muslim kingdom Ifat. See LEWIS, I. M.: The People of The Horn of Africa. International African Institute, London, 1955, p. 13. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Until 1972, the Somali language was a non-written language. |

| ↑3 | ABDULLAHI, M. D.: Culture and Customs of Somalia. Greenwood Press, Westport, London, 2001, p. 8. |

| ↑4 | FITZEGERALD, N. J.: Somalia. Issues, History and Bibliography. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., New York, 2002, p. 32. |

| ↑5 | ZAHORIK, J.: The Early History of the Somali and the Discussion on Baiso – an overview. In: Machalík, T., Zahorik, J. (eds.): Viva Africa 2007. Proceedings of the IInd International Conference on African Studies. Dryada, Pilsen, 2007, pp. 95-106. |

| ↑6 | Somali narrative history perceives this area as the original homeland of the biggest Somali clans. See ABDULLAHI, 2001, p. 8. |

| ↑7 | Earlier historiographies have taken the view that Somali people originated by mixing of the population of black Africa with the population of the Arabian Peninsula. Today, this theory is not an adequate scientific or academic explanation for the origin of Somalis and their history. However, it is not disputed that coastal cities existed and there was a continuity of relations between the two regions, but these links are not sufficient to form an entire ethnic group and the Arab migration to the Somali coast does not seem as strong as previously assumed. |

| ↑8 | Originally, this terms was the title for the Arab tribal leader (chief); later it was applied to the leaders of Sufi brotherhoods. |

| ↑9 | LEWIS, 1955, p. 14. |

| ↑10 | In this paper the term ‘Somali clans’ includes Somalis and Sabs. |

| ↑11 | An exception to this is the manuscript of the phonetic transcription of the Somali language, which had already been created by the ruler of the sultanate Majeerteen Cusmaan Yuusuf Keenadiid around 1920. This transcription is known as ‘Cusmaanya’ and was considered as one of the options for the modern standard form of the Somali language during the 1960s and ’70s. LEWIS, I. M.: Saints and Somalis. Popular Islam in a Clan-based Society. The Red Sea Press, Inc., Asmara, 1998, pp. 49-50. |

| ↑12 | FITZEGERALD, 2002, p. 48. |

| ↑13 | Somali democratic republic (1969-1991), President Maxamed Siyaad Barre. Since the overthrow of Barre, the official name of the country has been the Somali Republic. |

| ↑14 | JOHNSON, J. W.: Orality, literacy, and Somali oral poetry. In: Journal of African Cultural Studies, Vol. 18, N. 1, 2006, p. 122. |

| ↑15 | Ibid. |

| ↑16 | See ABDULLAHI, 2001, p. 73. |

| ↑17 | General Somali, sometimes called Northern Somali or North-Central Somali. For more information see JOHNSON, 2006. |

| ↑18 | Njogu, K.; Moupeu, H. (ed.): Songs and Politics in Eastern Africa. Mkuki na Nyota Publishers Ltd., Dar es Salaam, 2007, p. 362. |

| ↑19 | In this case I meant only strictly the Somali coastal areas, not for example coast of Swahili civilization, which has developed a writing system based on a synthesis of Arabic and Bantu language and could form a unique civilization stretching from the Somali Mogadishu to Mozambique Sofala (included forty cities) at the end of 13th century. The Swahili language had been written in Arabic script until 18th century and then it took the Latin alphabet. |

| ↑20 | Lewis compares Arabic spoken across the Somali region with the Latin of medieval Europe. See LEWIS, 1955, p. 11. |

| ↑21 | Poetic form traditionally does not exceed 100 verses. It has the character of the poetic form of pre-Islamic Arabia and even today enjoys huge popularity. |

| ↑22 | Memorable acts, hagiographic literature. |

| ↑23 | Warrior (literary spear-messenger). The term is applied to all adult men but does not include men who dedicate their life to God (see term wadaad). Women are also excluded from this classification and cannot become warriors. |

| ↑24 | LEWIS, I. M.: Understanding Somalia and Somaliland. Culture, History, Society. Columbia University Press, New York, 2008, p. 23. |

| ↑25 | Wadaad (pl. wadaddo) refers to men who are connected with religion, such as spiritual or ritual leaders, religious officials or members of Sufi’s orders. The term excludes warriors. Hierarchically, wadaad stands below the sheik (meaning sacred term), who express the highest spiritual and divine power and respect. |

| ↑26 | Records of the statements and deeds of the Prophet Muhammad. After the Qur´an, the second most important source of Islamic religious law. |

| ↑27 | Memorisers: see ABDULLAHI, 2008, p. 71. |