We are riding in an old battered Ford by the desert while the sun sets, after an afternoon swimming in Ain Sukhna – from the hotel´s beach resort. This is one of the few beaches in Egypt where mixed groups of young people are allowed to enjoy a sunny day by the sea. But there is a catch, mixed does not mean unmarried. ´So, Bara, now you are Paul´s wife if somebody asks you, and Ahmad is the husband of Christina…´ The organizer of our little beach expedition puts us into couples. This is so stupid, I think to myself. Anyone can try something like this, can´t they? I start thinking about that more and more on our way back to Cairo. I realized that this is the only way to allow premarital (not only sexual) relations for young Egyptians. Similar places have become an unofficial place for first dates, the first kiss and the beginning of real love, but also for the secret lover´s rendezvous, who are already married and simply fall in love with another person.

´It is a problem,´ explained Ahmad, on the way, to my classmates, ´if you go through the streets with your girlfriend hand in hand or arm in arm. We have to date secretly. If somebody finds out from my house or hers it will be the end for us.´ Another view, which I have heard on this topic straight from the mouth of Egyptians it was, that usually this happens in real marriages, so particular couples can enjoy their dating openly.

I am watching the passing road from the dusty window of the moving car, enjoying the last rays of sun before it disappears over the horizon of the Egyptian desert. A Christian rosary is swinging from the rear-view mirror with a slight curve and interrupts the ray of light shining on our faces. It´s a pretty nice coincidence that we are riding with a young Copt, Butrus (Peter). ´Butrus, can I ask you what you think about the fact that some people think that Copts and Muslims do not like each other?´ I asked Butrus. ´That is complete nonsense. I have a lot of Muslim friends, I have no problem with them and neither do they.´

Butrus, like every other driver in Cairo, gives me the impression that he does not actually pay attention to driving when he rests his right hand on the car window and the other hand is casually placed on the steering wheel. Driving is such a normality for most of the male population of Cairo as commonplace as breathing, although breathing was my first ´culture shock´ that I ever experienced, when I walked out from the air-conditioned Cairo airport. Sure, the classic example of ´culture shock´ for a central European student, who is raised on leafy avenues with the wind moving the trees in the ever-verdant parks. But that is not why I came here… Why do I still keep thinking about the disparities and differences between us and them? Why do I wonder about the fact that Coptic Butrus has a Muslim, Ahmad, as one of his best friends? Am I so influenced by the media stereotypes about religious conflicts in Egypt? Moreover, Ahmad also literally breaks my rigid ideas about the nature of young Muslims. This little culture shocks grows, and so I throw it behind my head and I feel a little ashamed of my naive romantic ideas about the far Orient and stereotypical notions about the rigidity of Islam.

Unlike Butrus, the tall Ahmad in a Ralph Lauren polo shirt, was more interested mainly in how many of us will go to a house party among the young Egyptians in the evening, where there are the familiar concepts of house music, ecstasy and other names of stimulants, empowering a night of uninhibited mingling and merriment. Of course, as in every other society, Ahmad found companions for this cultural diffusion.

Generally, it can be said that Ahmad belongs to a social group of wealthier middle-class Egyptians living in Cairo, who would never vote for such parties as the Muslim Brotherhood. Even though, it was this young blood, which set in motion the demonstrations at Tahrir Square, although the winners were the other parts of society. These young Egyptians, weaned on Western pop-culture, actively called for democracy and the promise of a liberalised lifestyle.

On the other hand, there were not so enough people to really change something. The start was pretty positive, inflamed, excited and very progressive, but did not last to the end. But there was a problem. Egypt is a country where army tanks swipe your friend in front of your eyes and dreams about democracy immediately disappear. This is the reason why it was so hard to change something.

Particularly, Egypt was among the first countries (just after Tunisia), in which was ignited the flame of popular demonstrations in the Arab world. From day to day, the bloody pictures of a murdered youth flooded social networks and became the impetus for several human rights happenings and demonstrations. My parents sent frightened emails to me in Cairo, with advice to be more careful, based on the latest news perspectives. The foreign journalists brought the latest events captured in the entire Tahrir Square and informed viewers hungry for sensation about mass demonstrations throughout Egypt. Throughout the whole of Egypt?! I answered in my email to my parents from a small remote internet café, surrounded on all sides by twelve-year old boys playing PlayStation. The flow of my thoughts was interrupted by the sounds of shooting games and the voices of the outdoor crowds of Egyptian football fans. Nothing to worry about, I replied.

I returned to my room with the other students and I passed by a corner Somali restaurant where older Somali men were sitting and smoking tobacco, carefully following what was going on their neighbourhood. The panel house where we were living was located about 15 minutes by taxi from the media dominated Tahrir Square. Honestly, if I had not turned on the television or opened my email inbox with warning messages, I would not have known that anything was happening (from just the surrounding localities where I spent time). ´Of course, I am just a cold fish when I am not so interested in a popular uprising and I do not want to contribute to it´, I admitted, mumbling to Paul. My puzzled roommate Paul shakes his head and starts eagerly explaining to me how important this demonstration is, since it is a long-awaited political transformation of the whole Egypt that will take place.

I totally understood Paul´s view. The whole thing suddenly came to be very important and personal from the moment when a few of his close friends died or were injured during the demonstration. It affects you a lot. He describes all the cases that had happened to young Egyptian students and more than a zealous commitment, a hopeless sorrow overcomes me. ´Do you really think that the demonstrations will change anything? The Islamists, populist or armed forces take advantage as usual.´ This was my nihilistic note. ´No, there is no chance, for example, for the Muslim Brothers to win. Nobody likes them and nobody wants anything like this. All of my friends are against them.´

But – they won. Actually, who were those of Paul´s friends? From his perspective of a Western college student, he chose people who were most similar to him. He has had too much to say to Egyptians who listened to rap, prefer going to house-parties, rather than to the mosque, or for example date some Western girls and ´knows what goes on in the West´. So, vice versa Paul was impressed by the breath-taking Egyptian women with deep black eyes which are highlighted by a dark scarf framing the contours of olive faces. He promised everlasting love to many girls (at least until the end of the student course).

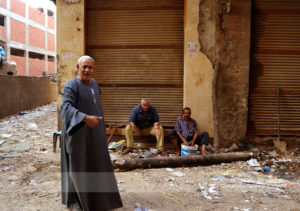

I have never wanted to downplay anything or detract from the importance of the autumn demonstrations in Tahrir, but I was not sure if the people who were demonstrating were the prevailing pattern of Egyptian society. I am starting to think about the poor oases and very needy suburb of Giza. Yes, this Giza, where Western tourists visit the world wonders and spend their money on a variety of commemorative souvenirs of the pyramids of Cheops. How many people visited these needy suburbs of Giza in Cairo and had the opportunity to know the real face of Egypt? I bought a banana shake there, which the street seller mixed in front of me in the dusty street. I enjoyed the idea of sipping something that would not reach any other Western stomach. I sipped the sweet cocktail from the street seller and I looked at him. ´I have never seen a tourist in this place. Where are you from?´ He was fascinated by me and I also by him.

I really enjoyed these moments – more than laying on the boring beach resorts. Overall, I admit that I have always appreciated Egyptian suburban people. These curious and ordinary people whose microcosm of everydayness was disrupted. There were kids on the streets playing football with one ball in ragged little trousers. They were followed by their mothers from windows who had only one wish – to give a better life to their children. This is the true face of Egypt, no nightclubs with golden youths from Zamalik, but shantytowns that grow and grow with frightening speed. This is the mass of people who were not in Tahrir just because they could not spare the time. The ordinary people who were trying sell something every day and save something for their families and firmly face poverty.

The demonstration became stale and Western journalists and cameras fixed their interest on other hot topics in the Middle East. However, some kind of Egyptian frustration has not disappeared and still exists. It could be said that Egypt, like many other countries is like a pressure cooker. There is still something here and it calls for emancipation. At the forefront of social networks calling for this freedom are young and angry youths, who want to make their country more inclined to the West. Behind them stands a silent mass of people, who try to survive every day and call only for social securities. On the other side, there are populistic and Islamist parties coming and responding to the actual situation with thrashed out slogans: Islam is the solution and distributing bread in the poor oases. Of course, everyone is aware that the Islamist parties are not panaceas. So, it is a cardinal question of what the future brings to this country with a population of more than 80 million.

I am watching the desert and following the sunset. I am looking forward to coming to my home and having a short shower and washing away the sand and salt from my body. Surely, I will listen again, as I do every evening: ´Mahmúd, Mahmúd! Why do you earned such little money?!´ This sentence will be followed by a brief altercation with the reproachful wife. Once the dispute dies down, the silence spreads through the panel house and into my open window will resound, falling through the muted sounds of Cairo´s rush hour streets. Like every night, I think to myself: How difficult it is to be a Mahmúd. To be an ordinary Egyptian.

Editorial Note: This article is based on author´s observations of Cairo from Autumn, 2011.