Malaysia is a country in Southeast Asia with an area of 329,847 km2. Part of the country lies on the Malay Peninsula and part on the island of Borneo. Malaysia gained its independence from Great Britain in 1957, and in 1963 it united with North Borneo. Malaysia is quite a multicultural country: Islam predominates but there are also Christians, Buddhists, Hindus and even animists – the Orang Asli people – who are the subject of this article.

Population of Malaysia

The majority of Malaysia’s population consists of three national groups: Malaysians, Indians and Chinese. However, a minority of the original inhabitants of Malaysia still live there. They are called Orang Asli, which can be translated as ‘indigenous people’ or ‘people of nature’, a name applied by people from outside that group. The Orang Asli make up approximately 0.6% to 1% of Malaysia’s total population and in 2012 they numbered 178,197 individuals.

Among the Orang Asli there are three language groups and 18 different tribes. The Orang Asli languages belong to the Austro-Asiatic language family. Many Orang Asli are bilingual today, speaking Malay as well. Their way of life is also changing, but some Orang Asli are trying to hold onto their identity.

The three groups of Orang Asli are the Semang, Senoi and Proto-Malay. Each of these ethnic groups contains six branches.

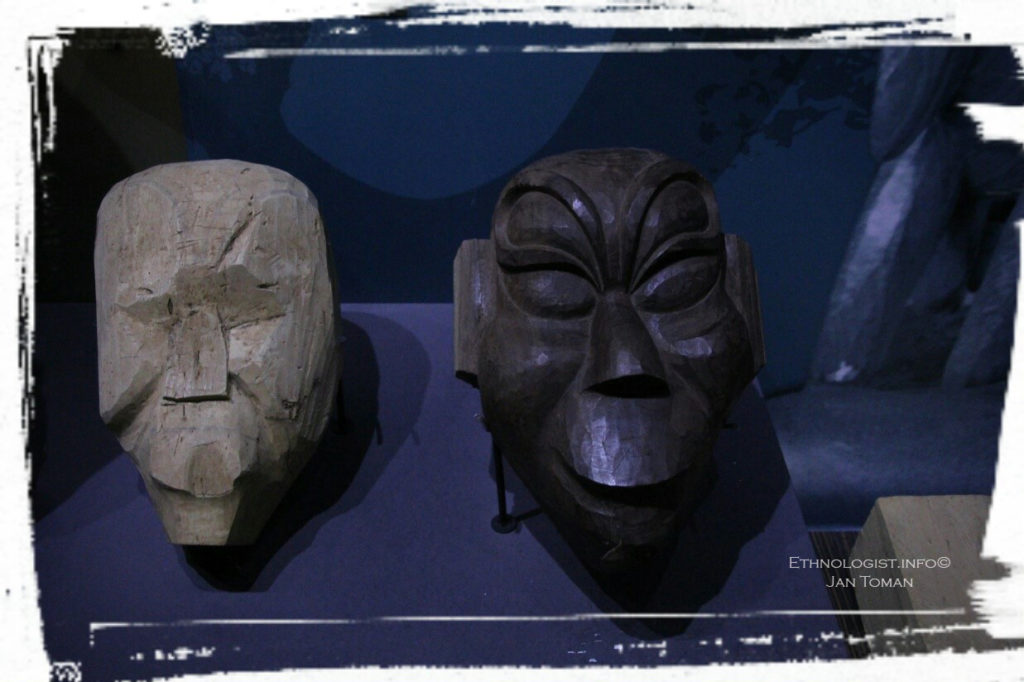

Orang Asli were originally animists, a belief system that some still adhere to, but some also follow Christianity or Islam. Their way of life is strongly connected to nature, which is clear from the way they hunt with blowpipes, or from their remarkable handcrafting of wooden masks, for which the Mah Meri and Jah Hut tribes are especially famous.

The dark history of the aboriginal people

The people of Orang Asli have a long history behind them, which was also very dark. At the beginning they were an isolated group of people who lived in the jungle and without contact with the outside world. The first contact probably took place around two thousand years ago, when they began trading with the first Indian traders who arrived on the shores of what is now Malaysia. The commodities the jungle provided were exchanged for salt, knives, axes and so on.

Ethnic Malays came to the Malay Peninsula from Indonesia and traded with the Orang Asli. However, there were also conflicts. For example, in the 18th and 19th centuries, when Malaysia came under the colonial rule of Great Britain, Orang Asli people were considered inferior and they experienced exceptionally hard times. Men were systematically executed, and women were sold into slavery. Gradually, they began to become the target of Christian missionaries or later the subjects for anthropological research.

From 1948 to 1960, Malaysia struggled with Communist uprisings. Orang Asli people were deployed as an important part of Malaysia’s army, which successfully managed to suppress the Communist insurgents. In the 1970s, significant industrialisation and modernisation began in Malaysia, which led to huge deforestation and land grabbing from the Orang Asli. In response, the Peninsular Malaysia Orang Asli Association (POASM) was formed, which mobilised the Orang Asli to make them more visible, and to strengthen their identity and cultural heritage.

Now, many Orang Asli live in great poverty. In some areas their traditional settlements of wooden huts are still in place but some are modernising their way of life and building classic brick houses. However, even the more modern members hold on to their traditional identity.

Traditional economy of the Orang Asli

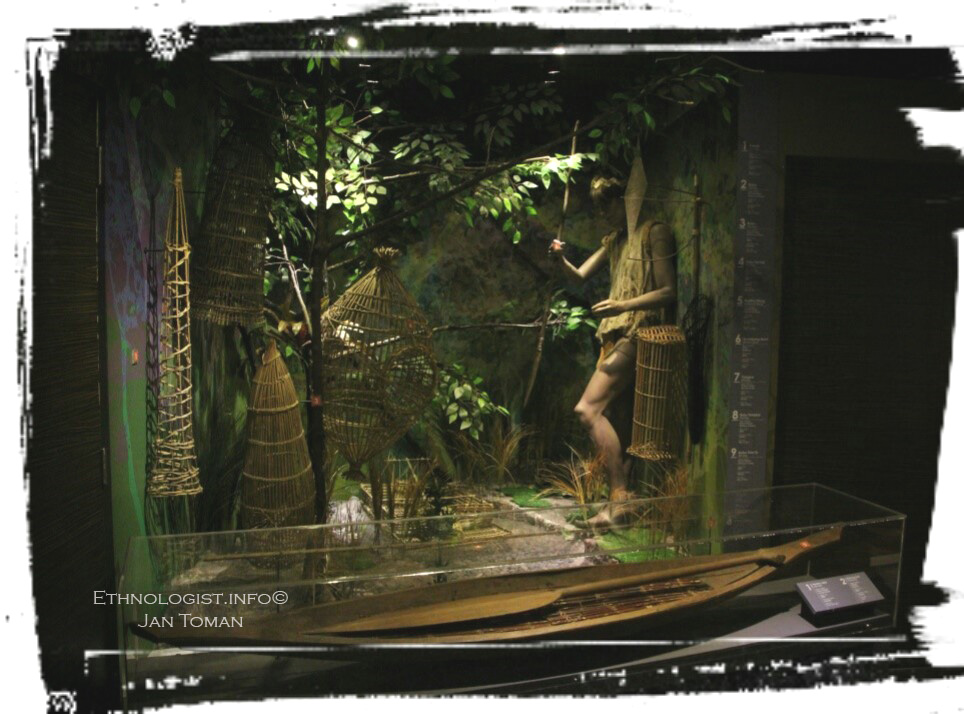

The traditional economy of the Orang Asli is based on gathering, hunting and fishing. To this day, the Orang Asli trade with important medicinal herbs which they find in the forest, which they use in a sustainable way. Moreover, the Orang Asli are allowed under law to collect protected plants and hunt endangered animals, including in the national park. Orang Asli use natural blowpipes for hunting larger mammals, such as monkeys or deer. These blowpipes are part of their cultural identity. For fishing, they use a kind of wicker cage as a trap to set in the water and then they wait for the fish to enter. These wicker cages are called ‘Bubu Wak’, ‘Bubuk Lu’ or ‘Bubu Che’o’.

Religion and the spiritual world of the Orang Asli

The Orang Asli were originally animists and their worldview is largely influenced by the environment they live in. Forests, mountains and rivers are considered important elements of their social cosmology and ritual taboos in their daily lives. Orang Asli shaman are called ‘poyang’. Their funeral ritual is also interesting: for some tribes the whole body of the deceased is wrapped in banana leaves and is buried in the ground. Other tribes practise cremation, building a pyramid of logs, called ‘galang’, and burning the body of the deceased at the top of it.

Their animist beliefs are also reflected in their material culture and their woodcraft. For example, the tribes of the Senoi group make figures that characterise their animist beliefs. The Orang Asli believe that events taking place in the spiritual world have a direct impact on their physical world and vice versa. The carved wooden figures have different functions and for tribes such as Jah Hut or Mah Mere they usually represent the spirits of their ancestors. Their distinctive carving skills also show their precise way of thinking and how they use geometric patterns, even though they do not use any mechanical tools.

The music of the Orang Asli

Music plays an important role in the life of the Orang Asli. It could even be said that music is their soul. They are inspired to make musical instruments from the natural materials provided by the jungle, and surrounded by the forest and its sounds they play music in perfect harmony with their environment. The Orang Asli believe that music will protect them from harm and evil spirits. Their instruments are divided into four groups, aerophones, membranaphones, chordophones and idiophones. The aerophones include the ‘bensol’ flute, which is played by the nose. The membranaphones are something like a special type of drum or tambourine, and the idiophones are small gongs.

My personal meeting with the Orang Asli

I visited the Orang Asli several times during my stay in Malaysia. Today the Orang Asli are a major tourist attraction in Taman Negara National Park. Travel agencies organise trips to visit them and tourists can try their blowpipes and other tools. However, often people who visit these villages question their authenticity and liken the local Orang Asli to film set extras so I decided to skip this place and visit a village in the Cameron Mountains instead. It was easy to find ordinary local people there – they are poor, but are still living traditionally and are representatives of original Orang Asli culture.

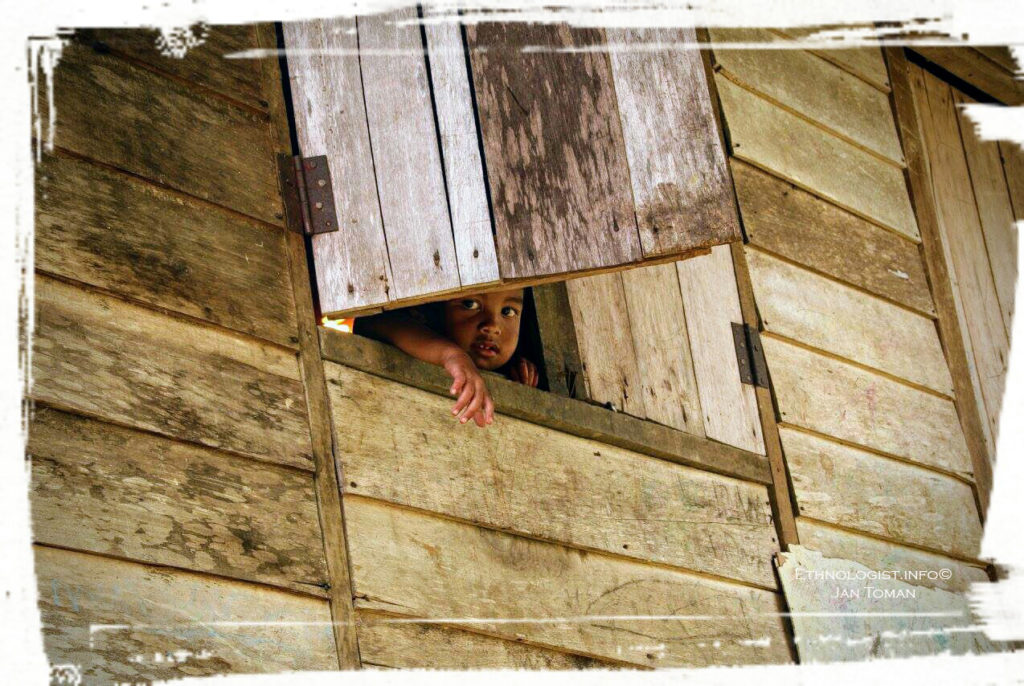

I discovered a village between the rainforest and the tea plantations near the town of Tanah Rata in the Cameron Highlands, where Senoi people live. Most of the village consists of simple wooden huts, often draped with washing. As a tourist, I didn’t feel very welcome so I tried to show the local people that I was interested in their culture and that I would like to look inside their house, for example, but the residents would not agree to this. Some of the children, however, could say “Hello, what’s your name?”

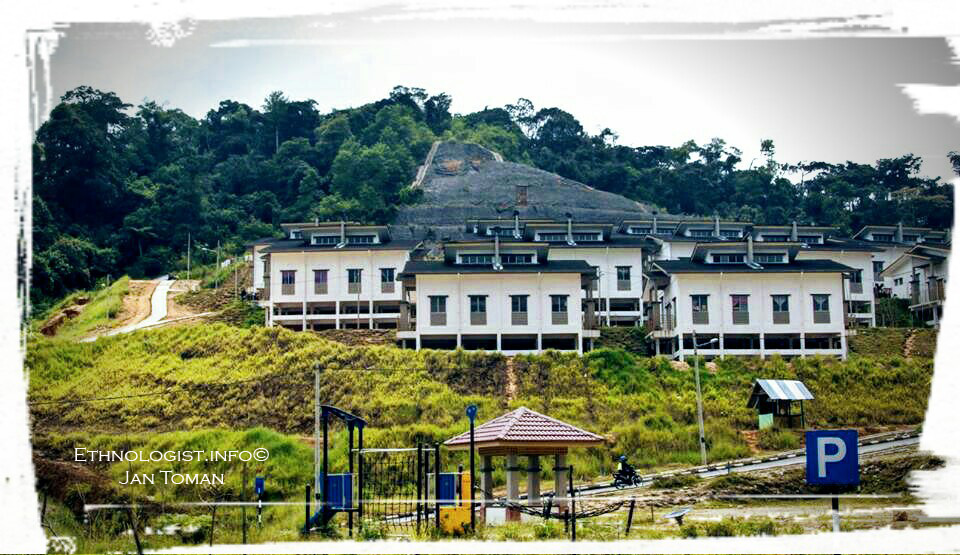

At the other end of Tanah Rata is a village where the Orang Asli live in modern brick houses, all of which have the same design and structure. The local people are still trying to keep their Orang Asli identities. I witnessed children playing there in a similar way to the children in the more traditional villages.

I also met Orang Asli when I volunteered in a family living just outside Kuala Lumpur. There’s rainforest just outside the city, which is where I met an Orang Asli man who spoke English, so I could converse with him. He told me about their spiritual world and I learned that they had “one god, who is present around everything in the rainforest”. In their world, he told me, there are two dragons, one underground and the other here on Earth. This man also showed me how he can play the flute using his nose (see photo above) and I even got to enjoy a traditional dish prepared in a jungle with him!

My third encounter with an Orang Asli village was in northern Malaysia in the province of Perak in the Royal Belum rainforest, which is where most of the Orang Asli of Malaysia live. This area seemed relatively poor to me. The Orang Asli are said to be advantaged in that only they have electricity here. When someone from the majority Malay population moves into the area, it can be much more difficult for them to get electricity. This was told to me by a gentleman who owns a restaurant on the main road leading over the hills, where I stayed for a couple of days. He was very positive about the Orang Asli, telling me that they supply him with various rare herbs, which he sells or uses in meals he prepares for guests, and that he goes to them for petrol. He took me to a village near a lake where the Orang Asli make their living mainly by fishing and from a petrol station. Here they were a little friendlier than in the Cameron Highlands but that may have been because they saw me coming with the locals.

Summary

Meeting the native people Orang Asli, who still live a so-called ‘primitive’ way of life, was an interesting and rare experience, considering that I met them in Malaysia, one of the most developed countries in Southeast Asia. The current Malaysian government is now trying to support the development of the Orang Asli ethnic group and is providing funding. I have seen them building modern brick houses using this financial support, but I have also heard about cases where the Orang Asli still prefer to build wooden bamboo huts in the jungle and practise a semi-nomadic way of life. In some villages, I saw that Orang Asli children had been given playgrounds and the Malaysian government is trying to give these children access to education. However, I was informed that only a very small percentage of their children complete primary school.

Malaysia is developing very fast, which can be quite challenging for Orang Asli people. Unfortunately, Malaysia’s rainforests are being quickly felled, but there are still large rainforest areas on the Malay Peninsula. Although Malaysia is a progressive and modern country, it is not very democratic. This affects the Orang Asli too, who struggle against mining companies that are encroaching onto their territory, threatening their traditional way of life. This is leading to a number of protests by the Orang Asli against mining companies, for example in Perak Province, as they work hard to stop deforestation.

The former Prime Minister of Malaysia, Najib Razak, who was accused of huge corruption and defrauding state funds, treated Malaysia’s largest national minorities, the Indians and Chinese, quite unfairly – but his stance towards the Orang Asli was rather more positive and he made efforts to support their education. Recently, a new political party won in Malaysia for the first time since independence from Great Britain. Malaysian citizens call this a political shift to ‘the new Malaysia’. The question is, how will this ‘new Malaysia’ affect the life of the Orang Asli – positively or negatively? Although I have seen that Orang Asli people are modernising in some areas, it seems to me that they tend to want to keep their identity and I do not think that any significant assimilation into Malaysian society will occur in the near future.

Interesting links

The Peninsula Malaysia Orang Asli Association

The Royal Belum State Park (UNESCO)

Translation from Czech to English: Barbora Zelenkova